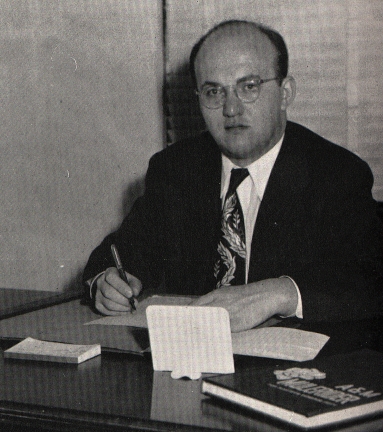

City University of New York Chancellor Robert J Kibbee, with glasses,looking on, in back at Groundbreaking of the new Kingsborough Community College Campus-President Leon M Goldstein and Brooklyn Borough President Sebastian Leone with shovels.-1974

From personal memories and the New York Times-

Dr. Robert J. Kibbee, (Bob) to his friends and colleagues was one of those rare and special people who quietly make a huge difference in the world around them and I will always remember him with fondness and pride .

He unfortunately passed away much to young at the age of 60. His death, after a long illness, came two weeks before he was to retire from the post he had held for more than a decade as Chancellor of the City University of New York, a university he helped save for all of us.

Whenever I pass by our college’s Kibbee Library or walk into it and see the small display of his life, lovingly curated and cared for by Tina Kopel , I think back to his many visits to KCC and his warm courtship of then KCC Professor, Margaret (Peg) Rockowitz and then later, Mrs. Robert J Kibbee.

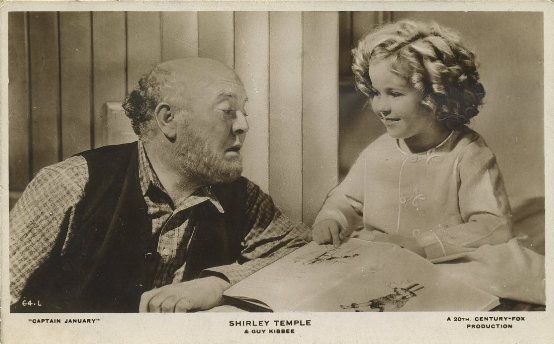

As most of you might not be aware Bob Kibbee was the son of the very famous and wonderful actor Guy Kibbee, whose movies many of us grew up with.

Dr. Kibbee’s father the great character actor Guy Kibbee

This was a very heavy burden for a young man striking out on his own and Chancellor Kibbee would often tell humorous and entertaining stories of his father and his time in Hollywood.

Dr. Kibbee’s tenure as chancellor of the country’s third largest university coincided with one of the most painful eras of the institution, which was set up in 1961 through the amalgamation of the city’s various publicly supported colleges.

The second year of the controversial policy of open admissions, under which the City University admitted all city high school graduates who applied, was just beginning as he took over the leadership in 1971 from Dr. Albert H. Bowker, who became chancellor of the University of California at Berkeley.

Dr. Kibbee, who had acquired most of his experience at selective private institutions, found himself called upon repeatedly to defend the City University from the attacks of critics. They charged that the university’s academic quality was being diluted to absorb thousands of freshmen who were inadequately prepared to enroll in an institution that until 1970 had maintained rigorous entrance requirements.

In his firm support for the university during those days of difficult transition, Dr. Kibbee showed the unflappable exterior that was to help him remain cool during the many crises that followed. Doing the Best You Can.

”You start from the point that you think you know what you are trying to do,” Dr. Kibbee said in discussing his ability to withstand the pressures of that period. ”You do the best you can and recognize that everything is not going to happen the way you want it to happen. There is always tomorrow and you shouldn’t look on every setback as a disaster.”

The decade proved to be a difficult time for all of American higher education, and Dr. Kibbee ended up having to guide the City University through a series of financial difficulties. He frequently was called upon to use his patient style to arbitrate conflicts over budget reductions.

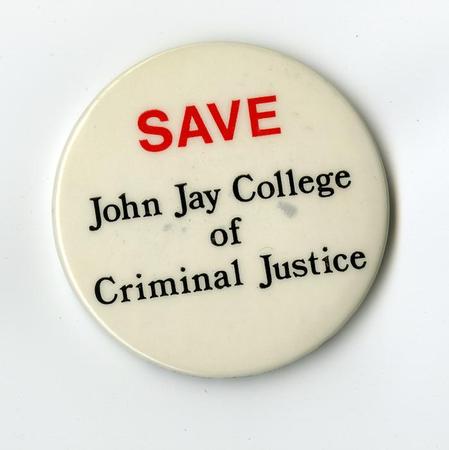

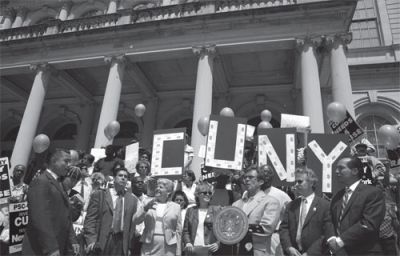

A 10 percent cut in the institution’s $550 million budget during the 1975-76 academic year set the stage for a lengthy drama. Several campuses of the 20-unit system were threatened with extinction, the institution’s suppliers were not paid and the entire university finally closed for two weeks in May, just as final examinations were approaching. Reneging on a Commitment.

To Dr. Kibbee, the worst part of the crisis was having to dismiss 2,000 faculty members who had been awarded new contracts just six months earlier. ”We had a commitment to them and then we reneged,” he said several years later. ”It just wasn’t fair, but the financial problem didn’t allow any other solution.”

The price of getting the university reopened was the abandonment of its cherished free-tuition policy. Through it all, Dr. Kibbee was a central figure, successfully resisting proposals for a takeover by the State University of New York and not shying away from political infighting when he thought it necessary.

This was a portent, and during the middle and late 1970’s, Dr. Kibbee found himself increasingly honing skills more characteristic of a politican than of a scholar.

He was confronted by a Board of Higher Education whose members often appeared, at least to the chancellor’s supporters, to subordinate academic needs to political considerations, and he found the appointment of presidents for the university’s various campuses to be a matter of keen interest among elected officeholders who were not averse to trying to influence the selection process.

In 1981, Dr. Kibbee announced that he would retire from the chancellorship , giving the trustees 14 months to find his successor. Although he had undergone cranial surgery several months earlier, he said the state of his health was not a factor in his decision, explaining: ”I’m not as active and agile as when I came here, but I’m 10 years older.”

The search for Dr. Kibbee’s successor, which began when he announced his retirement, was within days of completion at the time of his death.

Dr. Kibbee was a pragmatist who resisted efforts to cast his role as chancellor in philosophical terms. ”It’s always nice to think of yourself as the academic chieftain of an intellectually oriented body,” he said. ”But it costs money and takes buildings and equipment to have a university. This is the responsibility of the chief executive, and if you’re not willing to accept it, then you should stay out of this business.”

Opponents were often bemused and frustrated by Dr. Kibbee’s seemingly bland approach. The president of one of the university’s units theorized that the only signals that the stolid Dr. Kibbee, a rumpled six-footer, ever gave of his perturbance were a few extra puffs from his omnipresent pipe.

Even when his independence provoked both the Governor and the Mayor to seek his ouster, Dr. Kibbee remained mostly taciturn, accepting criticism in silence or, at most, delivering one of the dry witticisms that were one of his trademarks.

”If you can live long enough, you will outlast your critics,” he said to close associates on several occasions when the university faced adversity.

A lack of effusiveness, however, did not mean Dr. Kibbee was insensitive. He held fierce loyalties, was quick to voice compassion and was always among the first to commiserate with colleagues suffering personal problems.

Dr. Kibbee’s background may have helped develop his empathy with others. He was born on Aug. 19, 1921, on Staten Island, and his parents separated when he was a small boy. He carried both the blessing and the burden of growing up as the son of a famous father, Guy Kibbee, the actor.

His mother moved the family to Manhattan’s West Side, and the young Bob Kibbee became an inveterate New Yorker. He attended Xavier High School and went on to earn his bachelor’s degree at Fordham University, where the show-business connections established through his father won him a reputation for being able to get his friends into concerts by the popular big bands.

He went into the Army after his graduation from Fordham in 1943 and was serving in an antiaircraft unit in the Phillipines when World War II ended in 1945.

After his military discharge, Dr. Kibbee attended the University of Chicago, earning a master’s degree in 1947 in educational administration. His involvement in a lengthy study of higher education in Arkansas led to an appointment as a dean at Southern State College in that state.

In 1955, Dr. Kibbee moved to Drake University in Iowa as dean of students. He also resumed his studies at the University of Chicago, earning a doctorate in higher educational administration in 1957. He became an educational advisor in Pakistan.

Dr. Kibbee left Drake the following year to represent the University of Chicago as an educational adviser in Pakistan, a job that expanded to a three-year assignment and included membership on a committee that redesigned the country’s educational system.

He returned to the United States in 1961, joining the Carnegie Institute of Technology in Pittsburgh as assistant to the president, John C. Warner, whom he had known as one of the other consultants in Pakistan. In 1965, Dr. Kibbee was promoted to vice president and continued in a similar position after a merger that created Carnegie-Mellon University.

Dr. Kibbee was a surprise choice to head the City University, an institution unlike any with which he had been associated during his academic career.

Despite the public exposure associated with the $69,100 ( what a difference from todays salaries)-a-year job, he maintained a very private personal life, and few of those who worked closely with him were aware of his interest in the ballet or the enjoyment he derived from an occasional round of golf. Making Private Life Public

Dr. Kibbee himself took the initiative on one of the few occasions when his personal life became public. In 1973, he sent letters to each of the campus presidents in the City University and to the members of the Board of Higher Education telling of his separation from his wife, the former Katherine Kirk.

He was remarried in the spring of 1980 to Margaret Rockwitz, a faculty member at Kingsborough Community College in Brooklyn. The marriage took place while Dr. Kibbee was convalescing from cranial surgery for the removal of a tumor that was reportedly nonmalignant. He returned to work that spring, but even a year later still looked drawn and did not appear to have regained his former vigor.

In a commencement address he never got a chance to deliver, the week before he died, Dr. Kibbee counseled the graduating class at Brooklyn College to be humble and compassionate and to ”temper your judgments to the limit of your knowledge.” He did not appear at the commencement because of his declining health; his address was read to the 2,900 graduates at the Flatbush campus by Jerald Posman, a vice chancellor.

Dr. Kibbee, stressing to the graduates that the only advantage he had over them was longevity, said that ”what I have learned by living is that there is too much arrogance, simple-mindedness and indifference in the world.”

Robert Kibbee was a great and true friend to Kingsborough and to CUNY and was one of the key men responsible for saving the City University of New York, that is why I am so very proud every time I pass the magnificent Library named in his honor on our campus.