I was watching the great film “Hidden Figures” with my children about the African-American women who provided much of the mathematics and physics for the first space flights and moon landings for NASA.

My thoughts drifted to the often untold story of the women SPARS who supported the war effort during World War ll and did their training right here-where Kingsborough Community College now stands.

Many of them later served as the main operators of the top secret LORAN- long range navigation system throughout the European and Pacific theaters of naval operations.

During World War II The United States Coast Guard (USCG) Women’s Reserve, better known by the acronym SPARS trained hundreds of these women at the Sheepshead Bay Maritime Training Facility right where we today educate thousands of women for careers each and every day.

Yet I bet if we asked any one of them the history of the SPARS and who they were and what they did, none of them would know anything about these brave and courageous women or the sacrifices they made in order to join the military.

SPARS which stood for “Semper Paratus – Always Ready,” based on the Coast Guard’s motto.

The women’s branch of the USCG Reserve. It was established by the U.S. Congress and signed into law by the President Franklin D Roosevelt on 23 November 1942. This authorized the acceptance of women into the reserve as commissioned officers and at the enlisted level, effective for the duration of the war plus six months.

Captain Dorothy C. Stratton, Director of the SPARS during World War II

The purpose of the law was to release officers and men for sea duty and to replace them with women at shore stations. Dorothy C Stratton was appointed director of the Women’s Reserve (SPARS), with the rank of Lieutenant Commander and was later promoted to Captain. She had been the Dean of Women on leave from Purdue University, and an officer in The United States Naval Reserve (Women’s Reserve), better known under the acronym WAVES for Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service. Stratton is credited with creating the nautical name of SPARS.

SPAR Aileen Anita Cooke, apprentice seamen, is receiving her “boot” course at a United States Training Station, Manhattan Beach, Brooklyn, New York, 1941-1945.

The age for officer candidates was between 20 and 50; they had to have a college degree, or two years of college and two years of professional or business experience. The enlisted age requirements were between 20 and 36; candidates had to have completed at least two years of high school. For the most part, SPARS were white, but five African Americans were eventually allowed to serve. Most SPAR officers were general duty officers, but some officers received specialized training.

“To expedite the war effort by providing for releasing officers and men for duty at sea and their replacement by women in the shore establishment of the Coast Guard”.

First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt threw her support behind the women who volunteered to serve. The media used advertising to promote images of women in uniform and Hollywood made movies depicting beautiful starlets serving in the various branches of the armed forces. Thousands of women answered the call.

At first, according to agreement, the SPARS enlisted personnel received their indoctrination training on college campuses operated for such by the U.S. Navy. In March 1943, the USCG decided to establish its own training center for the indoctrination of enlisted recruits.

The site selected was the Palm Beach Biltmore Hotel,in Palm Beach Florida. Beginning in late June, all enlisted personnel received their indoctrination and specialized training there. Some 70 percent of the enlisted women who received recruit training also received some specialized training.

Yeoman and storekeepers represented the largest share, but many SPARS were given the opportunity to train in other fields. In January 1943, the training of enlisted personnel was transferred from Palm Beach to Manhattan Beach in Brooklyn New York where Kingsborough now stand

Two of the 5 African-American SPARS that were finally allowed to serve -pause on the ladder of the dry-land ship U.S.S. Neversail during their boot training at the U.S. Coast Guard Training Station, Manhattan Beach, Brooklyn, NY, during WWII.

The SPARS were assigned to every USCG district except Puerto Rico and served in Hawaii and Alaska as well. Most officers held general duty billets, which included administrative and supervisory assignments. Other officers served as communication officers, supply officers, barracks, and recruiting officers. The bulk of the enlisted women performed clerical and stenographic duties.

Enlisted SPAR Dolores Denfield, a parachute rigger during World War II

Mary Mills Weinmann in SPAR uniform, 1943-45

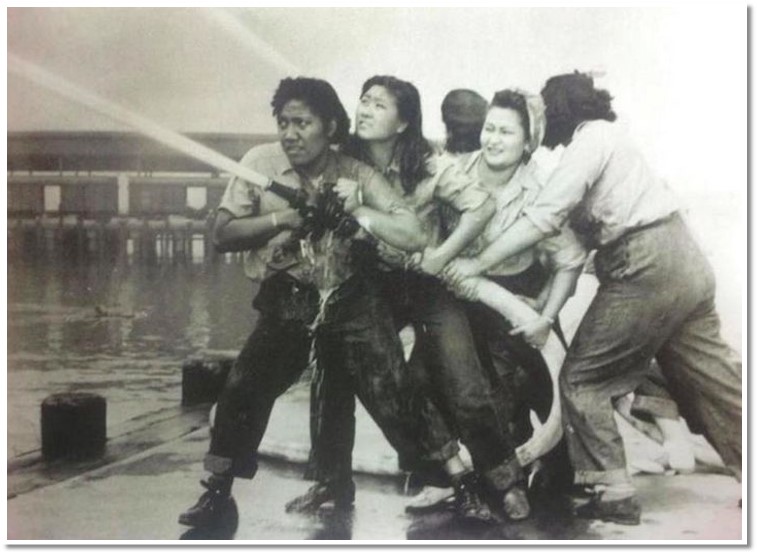

USCG SPARS in Training at Manhattan Beach Training Facility -November 1944

In smaller numbers, the enlisted personnel were found in practically every other billet, from baking pies to rigging parachutes and driving jeeps. A select group of SPAR officers and enlisted personnel were also assigned to work with the Long Range Aid to Navigation at monitoring stations in the Continental United States. Better known under the acronym LORAN it was a top-secret radio navigation system developed for ships at sea and long-range aircraft.

The first monitoring station staffed by SPARS was at Chatham Massachusets. Chatham is believed to have been (at the time) the only all female-staffed station of its kind in the world. The SPARS peak strength was approximately 11,000 officers and enlisted personnel. Commodore J. A. Hirschfield, USCG, said the SPARS volunteered for duty when their country needed them, and they did their jobs with enthusiasm, efficiency, and with a minimum of fanfare. To honor the SPARS, two USCG cutters were given their name.

Women were not to serve outside the continental United States, and no woman, officer or enlisted, could issue orders to any male serviceman.

Thanksgiving Dinner for the SPARS at the Manhattan Beach Training Facility.

In late 1942, recruiting requirements were such that both enlisted and officer candidates had to be American Citizens: have no children under 18 years of age; present three character references; pass a physical examination; and submit a record of occupation after leaving school. Enlisted applicants were also required to have completed at least two years of high school and be between the ages of 20 and 36 years.

Women SPARS at Manhattan Beach Training Camp are trained in Small Arms and Marksmanship.

Officer candidates were expected to be college graduates, or to have completed two years of college, and have at least two years of acceptable business or professional experience, and be between the ages of 20 and 50 years. Certain regulations with respect to marriage applied to both enlisted and officer candidates. Married women could enlist provided their husbands were not in the USCG. Unmarried women had to agree not to marry until they had finished their training period. After training, they could marry a civilian or service man who was not in the USCG.

In August 1943, recruiting policies were changed to permit SPARS to marry men of the USCG without having to resign. The USCG would continue to accept applicants who were married to men in the Army, Navy, or Marine Corps, but would not accept a woman who was already married to an enlisted man or an officer serving in the USCG. However, women could join the SPARS if their husbands were enrolled as temporary members of the reserve.

In November 1943, the marriage policy with respect to recruits was changed further to permit women who were wives of cadets, warrant officers, or enlisted men of the USCG to enlist or be commissioned in the SPARs. The ban remained on women whose husbands were commissioned officers in the USCG with the rank of ensign or above.

Although the USCG officially opened its doors to African-American women in October 1944, it was not until March 1945 that the first five women were accepted; they were the only African-American women to serve in the SPARS. Although the Women’s Army Corp(WAC) accepted African-American women from its inception, the U.S. Navy’s Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service (WAVES) only began accepting African-American women in October 1944, with fewer than 100 of them serving in the WAVES, and the US Marine Corp Reserve never opened its ranks to African-American women. The five African-American women who served in the SPARS were: Olivia Hooker, D. Winifred Byrd, Julia Mosley, Yvonne Cumberbatch, and Aileen Cooke.

“Our duties as SPARs were to fill jobs men had done to allow them to go overseas to fight,”

The average SPAR officer was 29 years old, single, a college graduate, and had worked seven years in a professional or managerial position (in education or government) before entering the service. The average enlisted SPAR was 24 years old, single, a high school graduate, and had worked for over three years in a clerical or sales job before joining the service. The likelihood was that she came from the state of New York Pennsylvania, Ohio or California. The reasons for becoming a SPAR differed, but most likely it was patriotism, self-advancement, desire for travel and adventure, or the loss of a loved one in the war.

In their off-duty hours, SPARS contributed time and effort to many community and wartime causes. Some became active nurse’s aides, some rolled bandages for the Red Cross others donated blood to blood banks, some visited service men in convalescent hospitals, and others collected gifts for the men overseas. Many of them were also involved in the March of Dimes campaigns, and war chest and war bond drives.Both officers and enlisted were awarded ribbons and medals based on their service, and some were acknowledged for their outstanding contributions to the SPARS and the country.In general, SPARS looked upon their service favorably, and many of them found a form of kinship in having been a part of the nation’s military forces during wartime.

With the surrender of in August 1945, the USCG demobilization effort began, and the SPARS were gradually discharged. They were separated from the service on a point system, and on the basis of their jobs. However, many SPARS were reassigned to the personnel separation centers to help with demobilization (women and men reservists) and they were not separated until it was completed. The Women’s Reserve of the USCG (SPARS) was inactivated on 25 July 1947.

An adjustment came when the SPARs were issued blue slacks and jeans. “That was the first pair of pants I had ever worn,” she said. “We wore them during KP (kitchen patrol/cleanup) and when it was uniform of the day.”

SPAR Olivia J. Hooker, of Columbus, Ohio, at the U.S. Coast Guard Training Station, Manhattan Beach, Brooklyn, New York, 1945

In his foreword to Three Years Behind the Mast, Commodore J. A. Hirschfield, USCG, observed that the SPARS asked no favors and no privileges. They did their jobs with enthusiasm, with efficiency, and a minimum of fanfare. The USCG was fortunate in having the help of the SPARS who volunteered for duty when their country needed them, and carried the job through to a successful finish. The USCG named two cutters in honor of the SPARS: USCGC Spar was 180-foot (55 m) sea going buoy tender commissioned in June 1944 and decommissioned in 1997, and USCGC Spar a 225-foot (69 m) seagoing buoy tender that was commissioned in 2001.

Although the SPARS no longer exist as a separate organization, the term is sometimes informally used for a female Coast Guardsman; however, it is not an officially sanctioned term.

One thought on “The Women SPARS Who Trained For War – A Rarely Told Story In History-Where Kingsborough Now Stands”