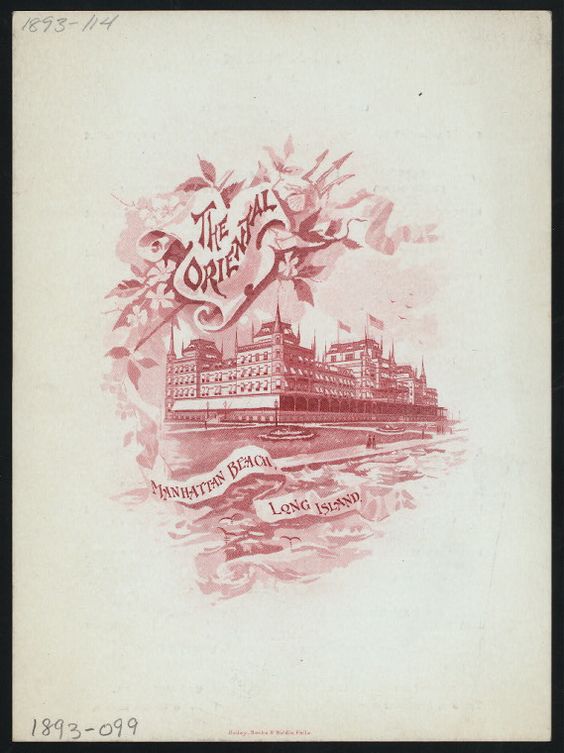

Tag: Oriental Hotel

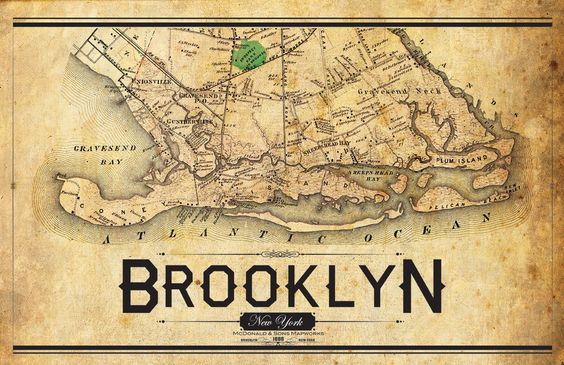

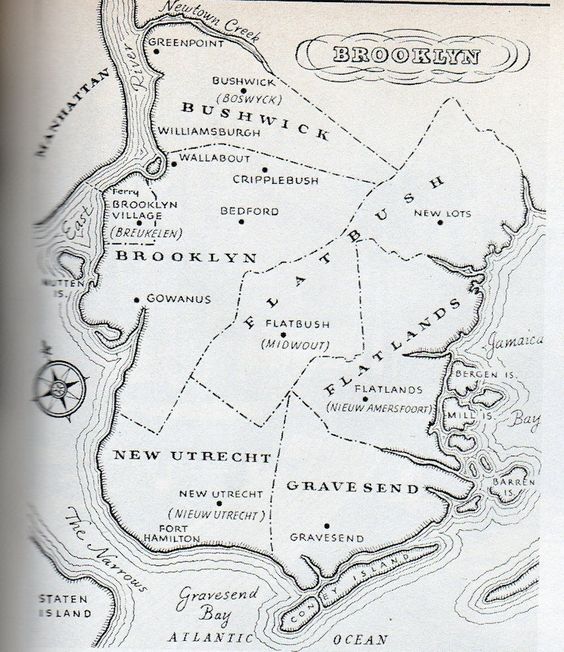

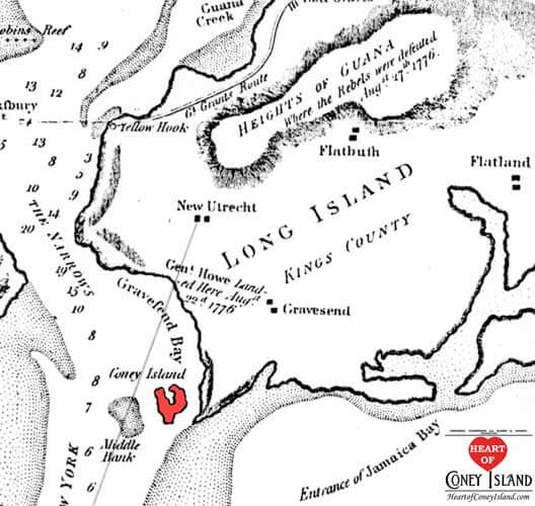

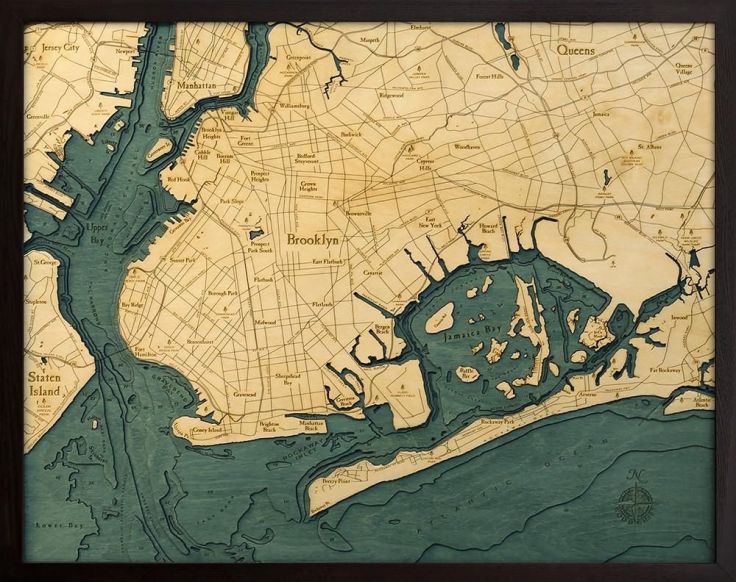

The Changing Shape of the Point at the End of Brooklyn-The Manhattan Beach/Kingsborough Peninsula 1600-2017

Pre- 1600’s -Occupied by Canarsee Native Americans of Lenni Lenape Tribe- a hunting fishing area where Native Americans collected Oysters and Clams from Jamaica Bay.

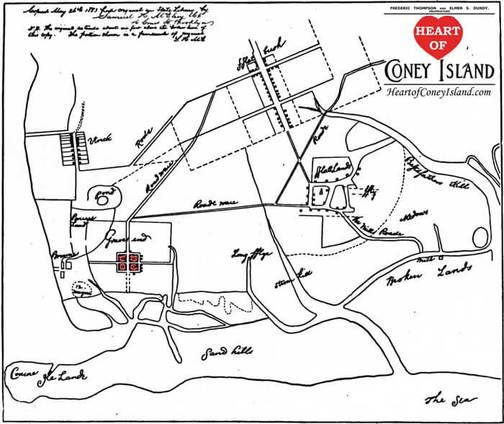

1600’s Dutch -The Sedge Bank- a large swampy area at the eastern most point of Coney Island.

1600’s -Sedge Bank- a swampy area at eastern end of Coney Island used by smugglers and pirates.

1600’s- Coney Island named for the Dutch Word for Rabbit

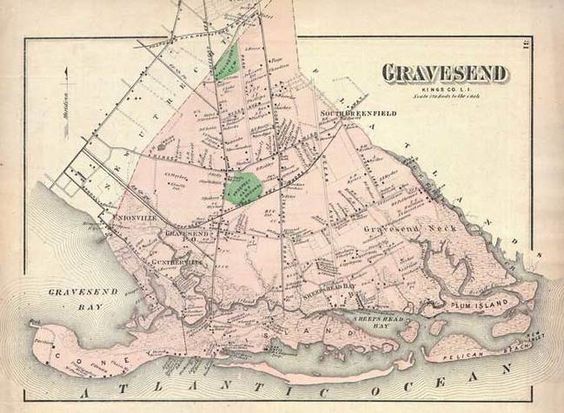

1700’s- Township of Gravesend-deeded to Lady Deborah Moody

1700’s- Sheepshead Bay- named for the Fish, with the highly unusual human teeth.

1700’s -Sheepshead Bay

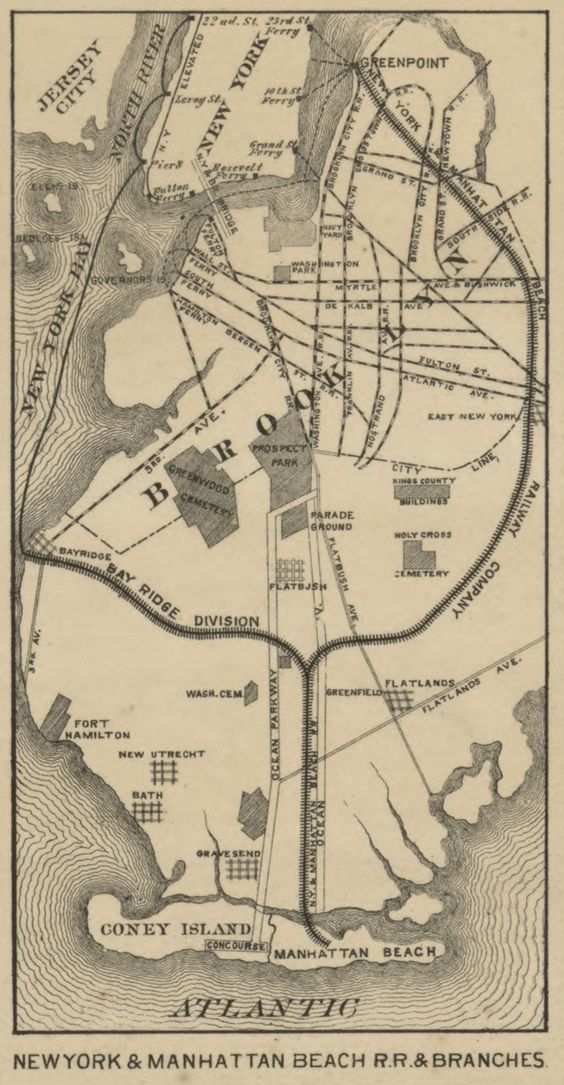

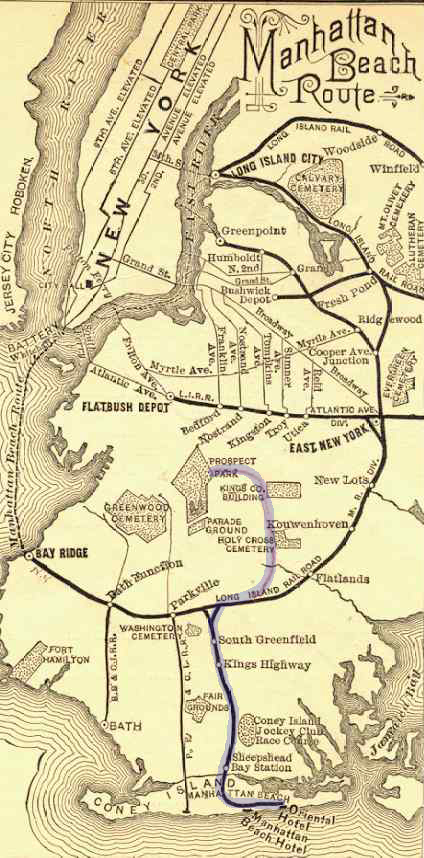

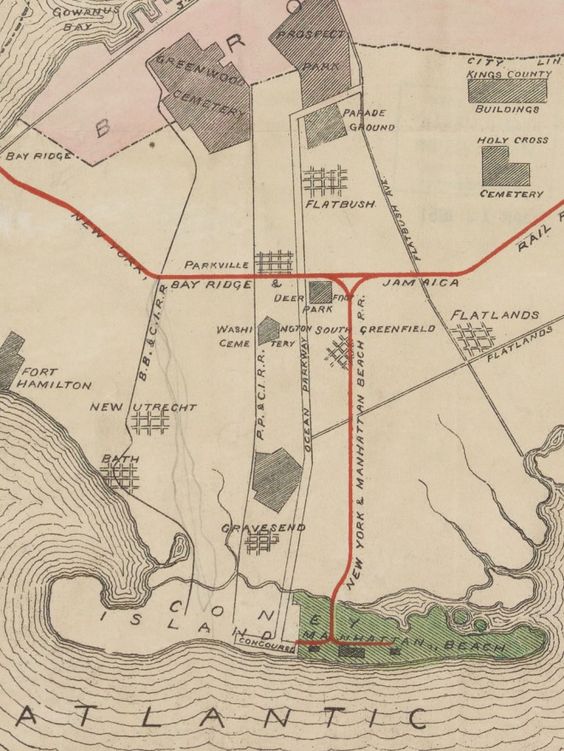

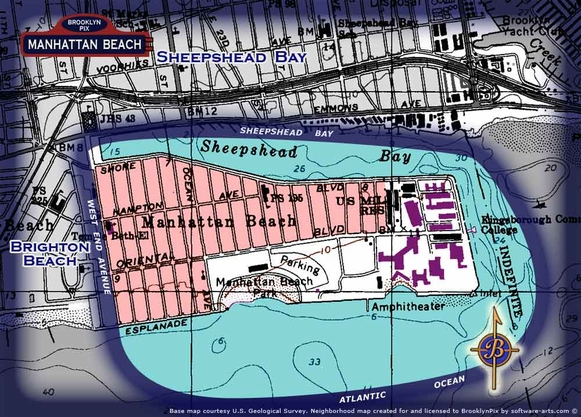

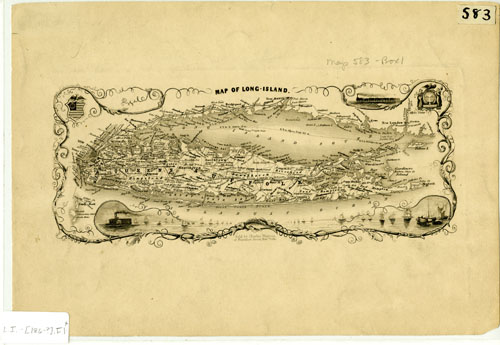

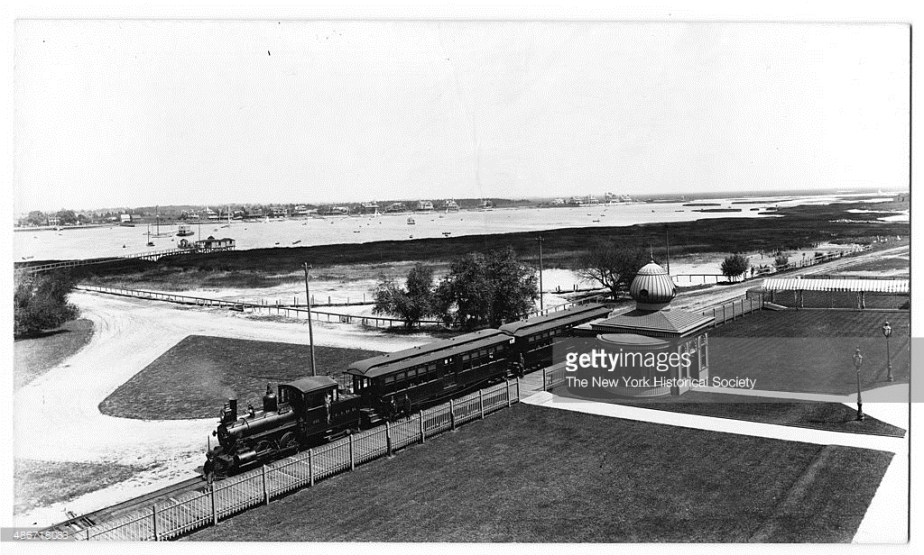

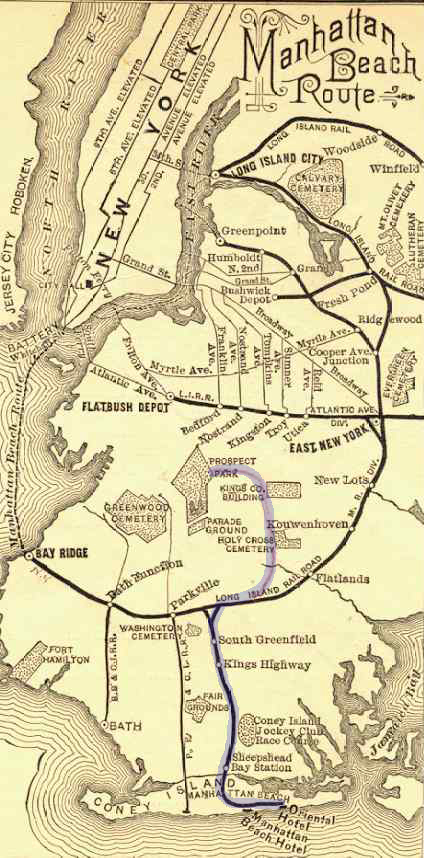

Late 1800’s Manhattan Beach Railroad Map to Manhattan Beach and Oriental Hotels at eastern point of Coney Island.

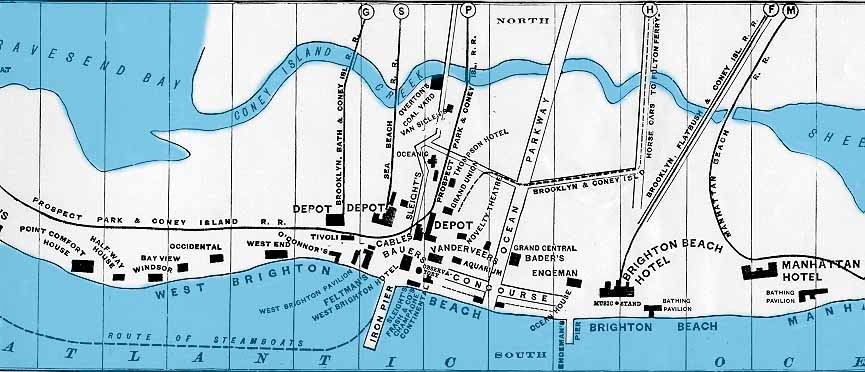

1879- Approximate Locations of Manhattan Beach and Oriental Hotels.

1890-Map of Manhattan beach and Oriental Hotels

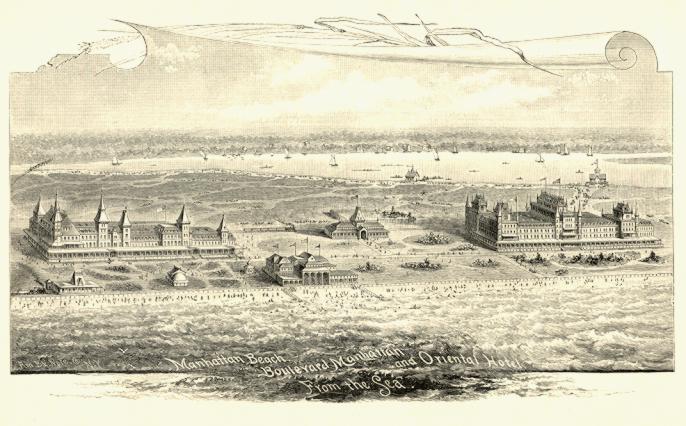

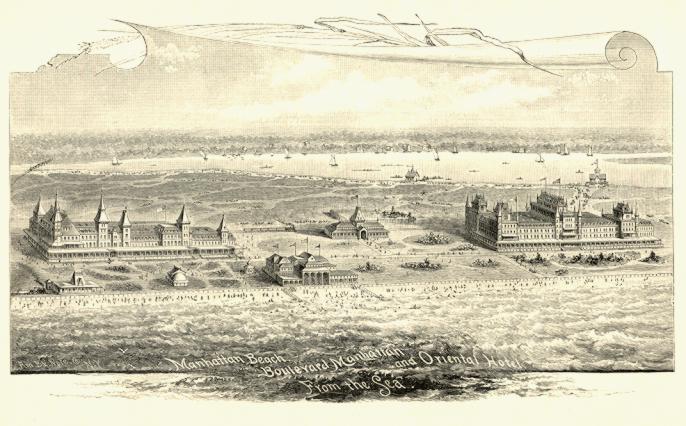

1894- Photo of Manhattan Beach and Oriental Hotels

1880’s- Manhattan Beach and Oriental Hotels

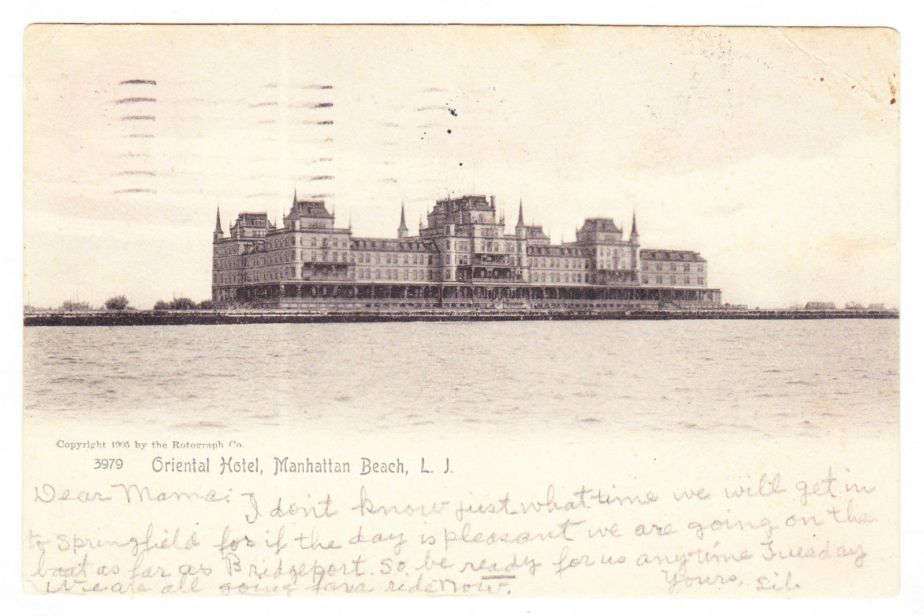

1897- Manhattan Beach and Oriental Hotels

1897- Manhattan Beach and Oriental Hotels

1910 View of Coney Island from Balloon

1921- View of site where Kingsborough now stands.

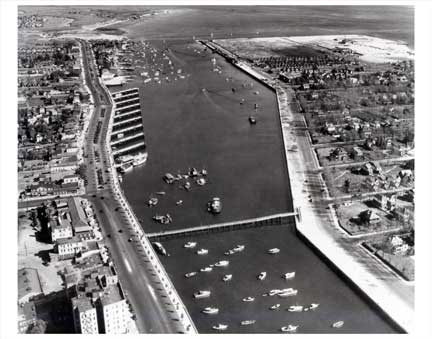

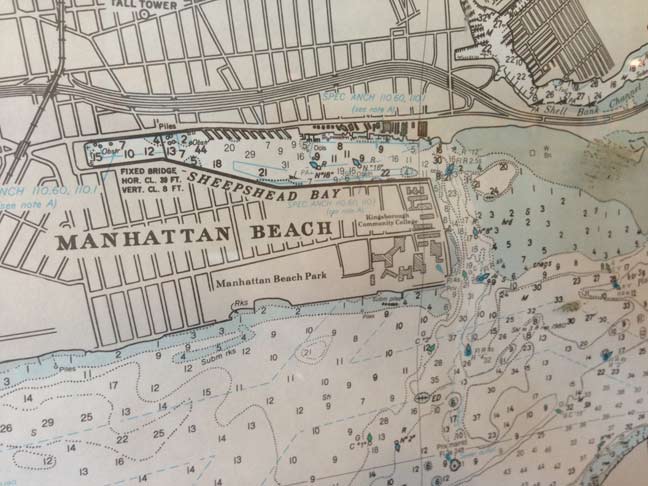

1922 View of Sheepshead Bay and Manhattan Beach

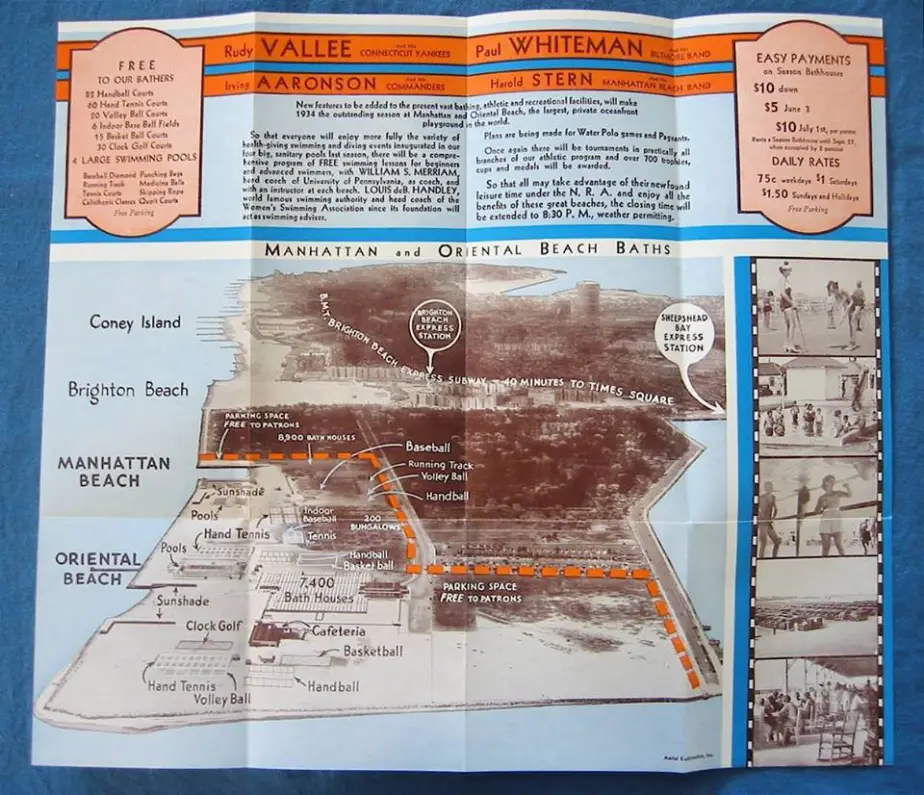

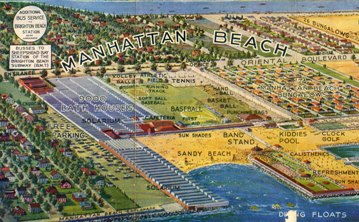

1932- Manhattan Beach Baths

1934- Manhattan Beach Baths

1934- Manhattan Beach Baths

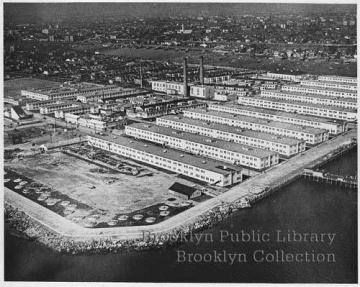

1946 Sheepshead Bay Maritime Training Facility

1946- Sheepshead Bay Maritime Training Facility from Blimp.

1946- Sheepshead Bay Maritime Training Facility

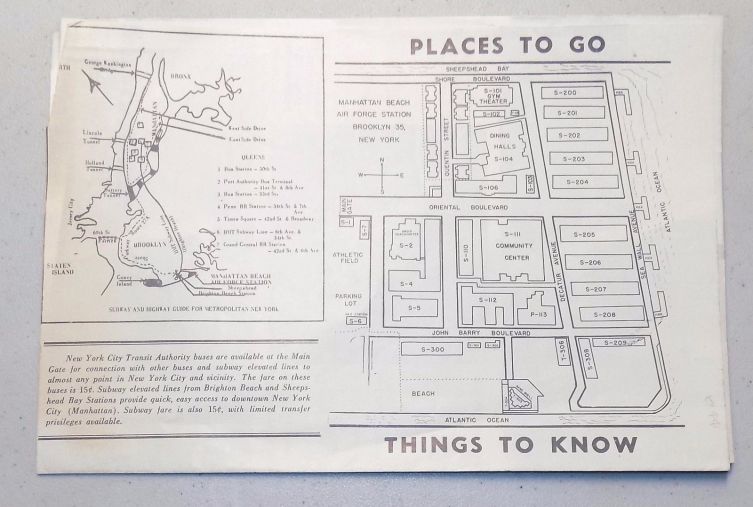

1947- United States Air Force Training Facility

1959 Occupied as Housing for US Military

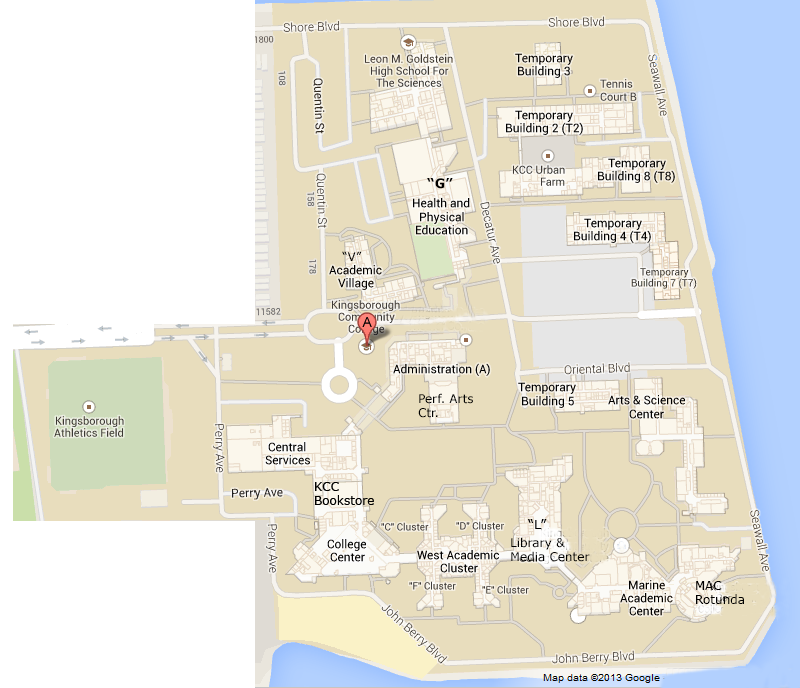

1967- Abandoned Military Base Occupied by Kingsborough Community College

1967- Kingsborough Community College

2015- Kingsborough Community College

2015- Kingsborough

2015- Kingsborough

2015- Kingsborough

2017- Kingsborough Community College

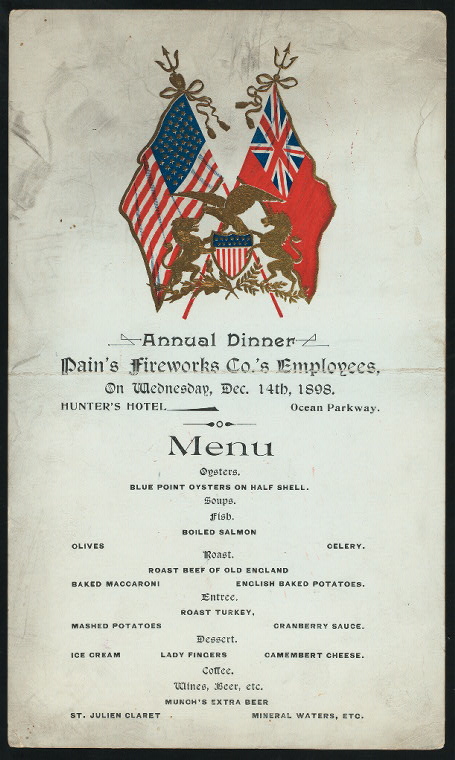

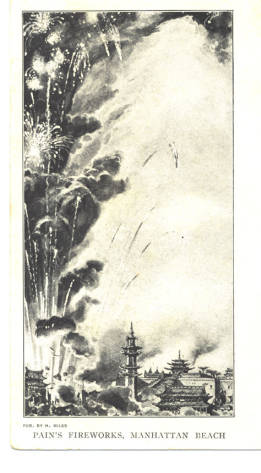

Fireworks by Pain at Kingsborough Community College (Manhattan Beach) in the 19th Century

Fireworks are one of our most enduring customs, and have moved us for centuries. Each dazzling display depends on a simple technology, a black powder known as gunpowder, an explosive mixture that shoots fireworks into the air and propels bullets from guns.

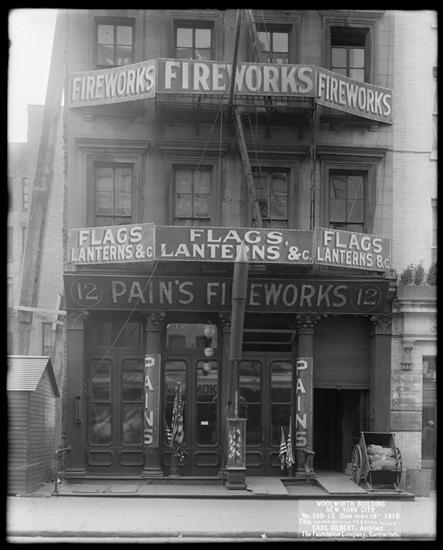

12 Park Place, one of the prominent retailers of explosives along ‘Firecracker Lane’. James Pain was known as one of the world’s greatest pyrotechnists. Today the Pain name lives on in a UK fireworks company.(Wurts Brothers, courtesy MCNY)

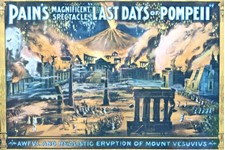

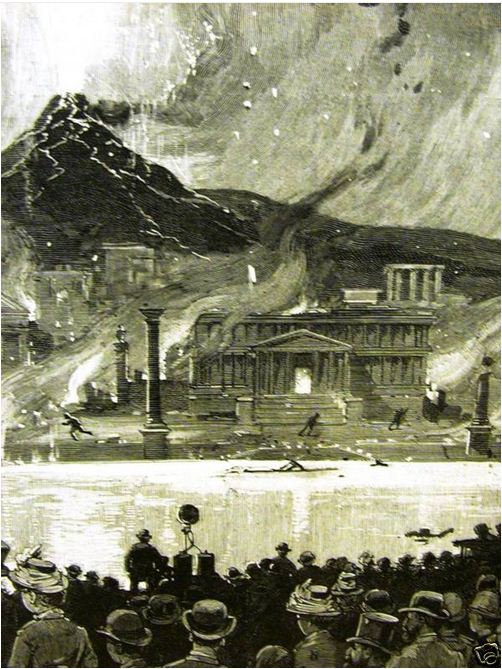

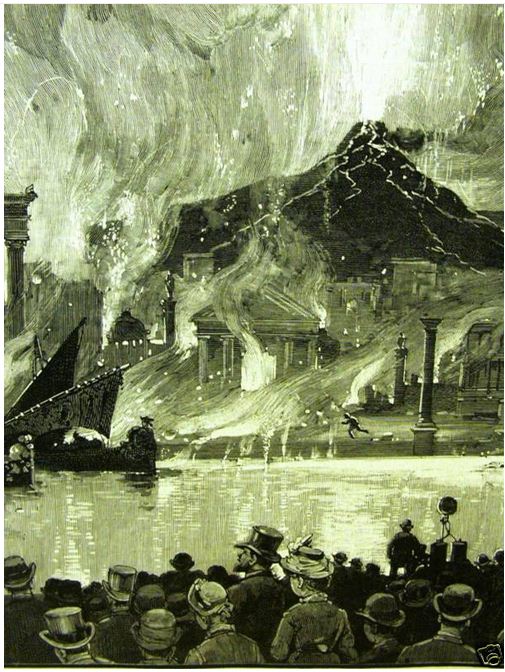

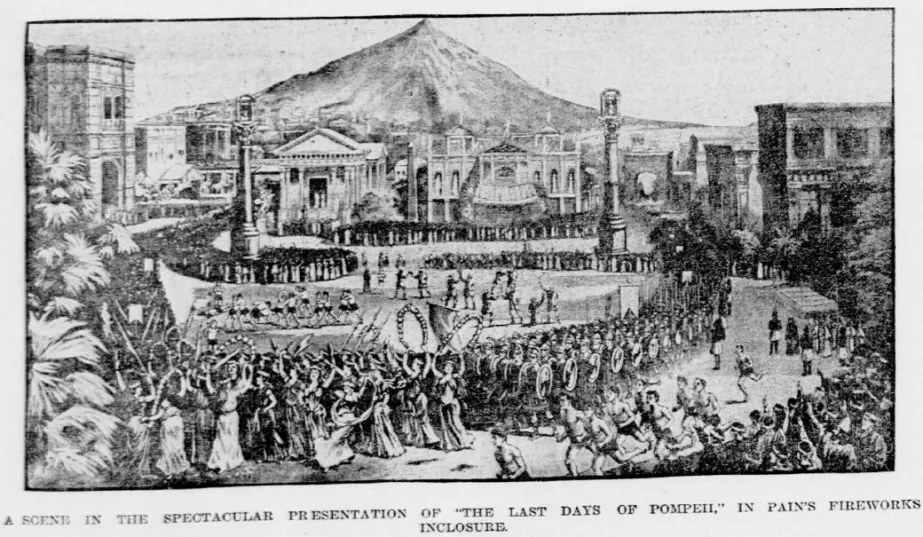

Between the two grand hotels – the Oriental Hotel and the Manhattan Beach Hotel now (Kingsborough Community College) Behind the latter, stood an enormous fireworks amphitheater – complete with man-made lake and dedicated fireworks factory – played out demonstrations. The operators, father and son team James and Henry Pain, were particularly fond of extravagant historical tableaus (the lake was used to recreate naval battles), and created shows like “The Battle of Gettysburg,” “Siege of Vera Cruz,” “The Burning of Rome,” “The Attack of Moscow” and “The Last Days of Pompeii.”

It was the Chinese who first discovered gunpowder over 1000 years ago. Soon they developed simple pyrotechnics, like firecrackers, which they believed had the power to scare away evil spirits. Marco Polo said these devices made such a dreadful noise that anyone not used to it could easily go into a swoon and even die.

The most important ingredient in gunpowder is the compound potassium nitrate, more commonly known as ‘saltpeter.’ These naturally-occurringcrystals are not explosive on their own, but require the presence of a fuel, like charcoal, to produce a flammable mix.

Ancient alchemists refined the recipe to 75 percent potassium nitrate, 15 percent charcoal and 10 percent sulfur. The ingredients become explosive after they’re ground together. This highly volatile black powder gave birth to the science of pyrotechnics and the incredible fireworks we experience today.

The wood carvings depict that last one, in which the ancient Roman city of Pompeii is consumed by the lavas of Mt. Vesuvius. The show ran for quite some time, at least from 1885 – when the illustration above was published – to 1903, when a New York Daily Tribune profile of Manhattan Beach made reference to the performance. But, from the brief research we did, it appears all of the historical performances – which were held daily during intermissions for concerts by Patrick Gilmore, John Philip Sousa and Victor Herbert – were handled by the younger Pain, who managed the set from 1879 until 1905; it’s likely “The Last Days of Pompeii” ran just as long.

The performances were more than just a fireworks display. Live music played as costumed actors, clowns and acrobats entertained, and then ultimately scrambled for cover as the fireworks began exploding, simulating the volcano’s mighty eruption.

But not all the actors were professionals. In this 1903 account from the New York Times, a man named Jefferson Jackson was hired for a minor part in the performance. But Jackson, “a burly colored member,” wasn’t told what the role entailed.

Where Jefferson is now Mr. Pains wants to know. He was last seen negotiating the course between the fireworks amphitheatre and Sheepshead Bay in record-breaking time clad in a costly, bespangled garment, and with a stream of flame behind him.

Jackson was an Alabama negro just from the plantation, and when he was hired to carry a torch in the “Last Days of Pompeii,” nobody explained to him the nature of the spectacle. When Mount Vesuvius went of Saturday night Jefferson Jackson went likewise.

He carried what is known as a lycapodium torch, which, whirled in the air, causes a flambeau effect. The faster Jackson ran, the greater became the flame from the torch until as he rushed along the board walk to Sheepshead he looked like a traveling flame. He did not appear for rehearsal yesterday.

What happened to Jackson we may never know. But the prodigious Henry Pain continued to be an American star of the pyrotechnic world, known as “The Fireworks King.”

The Brooklyn Eagle did a nice little bit on his work last year:

[Pain] traveled to France for the 1900 Paris Exposition, or World’s Fair, then back to America for the Pan-American Exposition at Buffalo in 1901 the St. Louis Fair in 1904.

At the Buffalo celebration shortly after the Spanish-American War, he created an aerial display of a map of the USA including our latest possessions, Puerto Rico, Cuba and the Philippine Islands. For the finale, the likeness of the President, William McKinley. While attending the fair later, McKinley was assassinated and the former New York governor, Theodore Roosevelt, stepped into the office. Later, Pain also created portraits in fire of Presidents Roosevelt, Wilson and Taft.

Before Henry Pain died in 1935, he was interviewed for The New Yorker by James Thurber for the July 4, 1931, issue after 27 years in the fireworks business. In the article, Thurber revealed that the largest display of fireworks set up by Pain’s company was for the Havana inaugural of President Machado in Cuba in 1929. Over $25,000 of fireworks were shipped there, perhaps enough to sink the battleship Maine all over again. Every rocket and explosive device was set off in less than two hours. Thurber reported that the largest and most expensive piece was a replica of Havana’s new capitol which was 70 feet high and 700 feet long, costing $6,000 but lit up for only a few minutes.

Black powder is a mixture of three components, potassium nitrate, sulfur and charcoal. If you mix them together you end up with a powder in which you can still see the white, yellow and black flecks. Now if we burn that, what happens is it burns relatively slowly.

This is really quite useful for the basis of a lot of firework compositions where you want something to burn slowly enough that you can see it in the air. If it burnt too quickly it would all be over and it would be a pointless firework. So lots of sparks being produced slow, burning lots of gas, lots of smoke.

And if you take that same chemical composition but you grind the potassium nitrate and the charcoal together, add the sulfur, grind it over many hours, press it into cakes, break it up, you end up with a powder the consistency of coarse granulated sugar.

Now when we burn that, the fire can travel both through the grains and between the grains and the whole reaction is very much more quick. This sort of thing is used for making the lifting charges of fireworks, where you want lots of gas in a short space of time.

So if you take the same black powder but compress it into a tube, what we get is, in effect, a little fountain. It only burns on the top surface.

his same black powder can be compressed into marble-sized balls, called stars. They’re used in many of the shells in large-scale displays like Boston’s 4th of July celebration. Each star-filled shell is ignited by an electronic match inserted into the lifting charge in its base.

This is a typical chrysanthemum shell that will be fired during the program. At the base of the shell is a black-powdered lift charge. Once that is ignited, it will propel the shell approximately five or six hundred feet into the air. Then there’s a secondary burst that takes place within the ball shell. It will then ignite several hundred small marble-sized stars that will determine the shape, which will be round in symmetry because this is a round shell.

Round shells can also create waterfalls, ring patterns, strobes, titanium salutes and peonies. Roman candles and fountains come from tubes.

The modern firework display is full of color. And you make color by adding metals salts, not metals but metal salts to the composition. So, you know, if you put a piece of copper into a fire you see it glow with a blue flame, and we can do the same. It’s the sign of a very good firework-maker is a really good strong blue. And here we’ve added copper oxychloride to the basic oxidant fuel mix and we get a good blue flame.

Adding strontium salts to the mix makes a red flame. And adding barium to the mix makes a green flame. So with those three, and with other metal salts, we have a whole spectrum of colors that we can use.

The Bicycle Phenomena of the Late 19th Century and Kingsborough ( Manhattan Beach, Brooklyn)

In the 1880s, Manhattan Beach, Brooklyn had the countries first designated Bicycle Stadium or Velodrome and Ocean Parkway became the country’s first designated bike path, with thousands of “wheelmen” and “wheelwomen” pedaling the six miles from Prospect Park to Coney Island.

When a second Ocean Parkway path was completed in 1896, the New York Times described opening day, June 28, poetically:

“Over the return cycle path, in Brooklyn, which lies like a strip of gray ribbon from Prospect Park to the sea, there rode yesterday an army of cyclists. There were all sorts and conditions among them—the grave and the gay, side by side, each bent on doing his share to celebrate the formal opening of the second path in the Imperial Ocean Boulevard.”

Bicycles were like the iPhones of the 1890s.

Manhattan Beach Brooklyn Bicycle Stadium 1890’s where Kingsborough Community College now stands.

Heavyweight Champion of the World “Gentleman” Jim Corbett tries out the Manhattan Beach Bicycle Track before fight .

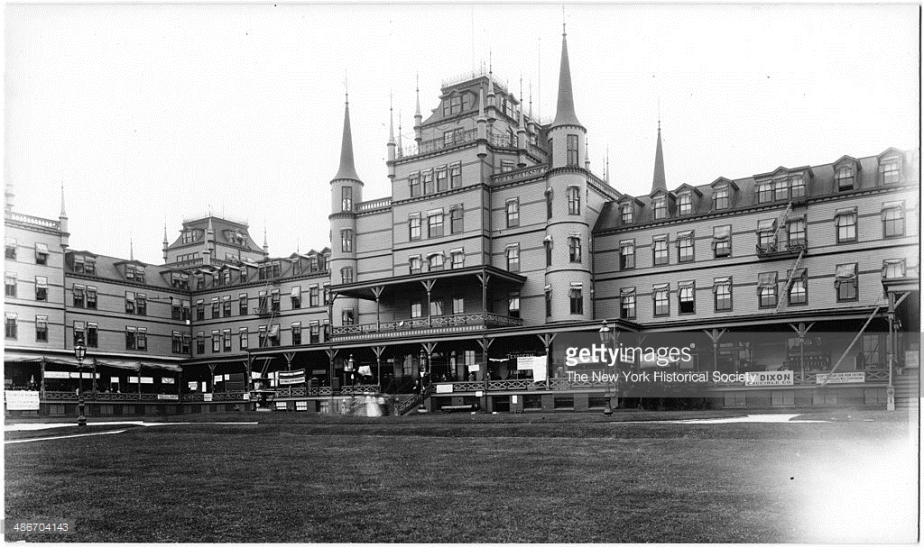

The Manhattan Beach Hotel opened for business in the summer of 1877. Built by architect J. Pickering Putnam, the four-story Queen Anne-style wooden hotel was nearly 700 feet long, featuring distinctive turrets and covered verandas with neatly manicured grounds surrounding the hotel and facing the boardwalk. The hotel had a grand reputation from the moment it opened former president Ulysses S. Grant presided over its open ceremony on July 4 of that year. The Brooklyn Daily Eagle called it “the best hotel on the Atlantic Ocean.”

Notice sign on left-for Bicycle Stadium in Manhattan Beach, Brooklyn.

It would have been difficult to disagree: the hotel featured the nations first bicycle track for professional and amateur racing, 150 guest rooms as well as an assortment of restaurants, ballrooms, and shops and offered first class entertainment.John Philip Sousa performed here and wrote the musical piece “The Manhattan Beach March” in the hotel’s honor in 1893. In addition, exclusive New York clubs such as the University Club, the Union League, the New York Club and the Coney Island Jockey Club used the resort as their summer headquarters. Based on the success of his first hotel, Corbin would build another three years later?the Oriental Hotel. An opulent hotel with a Moorish motif, this hotel catered to the wealthiest of families, offering them suites for extended stays throughout the entire resort season.

On the sunny and cool afternoon of June 17, 1896, a parade was held in Brooklyn celebrating the opening of the Ocean Parkway cycle path. At one p.m. sharp, the inimitable sound of ten thousand approaching bicycles filled the air. Spearheading this procession was the noted rider Charles H. Luscomb of the Thirteenth Regiment, accompanied by a military entourage of three hundred militiamen. They were swiftly followed by the uniformed personnel of more than thirty cycling clubs drawn from across the region, including the Amsterdam Wheelmen and the Ninth Ward Pioneer Corps. Next came the serried ranks of the League of American Wheelmen, the largest cycling organization in the country with more than 100,000 members. Concluding this cavalcade were thousands of “unattached” cyclists ranging from gaily-bedecked children to fashionable couples, whisking their way down the boulevard on their “silent steeds,” past the undeveloped meadows of central Brooklyn until finally reaching the sun, surf and sand of Coney Island.

This was the most magnificent cycling parade New York City had ever seen, a celebration of the country’s first bicycle path, opened to answer the demands of the expanding crowd of New Yorkers with wheels. For in the mid-1890s, New York was the “Metropolis of cycledom,” in the words of the Brooklyn Eagle, home to 250,000 bike-owning citizens (or one out of every twelve New Yorkers), ten cycling journals, fifty-five cycling clubs in Manhattan alone, twenty-nine cycling academies, and cycling racks everywhere from Madison Square Garden to the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The earnest debates on the moral and political consequences of cycling were held in esteemed newspapers and at great public meetings.

And yet, no more than five years later, the bicycle would be abandoned by Gotham’s citizenry as quickly as it had been taken up. It would remain out of fashion for most of the next century, until it became object of a new, but markedly similar, craze; a fin de cycle story that should serve as both an inspiration and a warning to riders and cycling advocates today.

In the 1880s, bicycles had attracted small groups of dedicated practitioners, but the product’s poor safety record, extensive learning curve and relative obscurity kept the ranks of wheelmen limited. The invention of the “safety” bicycle in the late 1880s, however, changed this; its two same-sized wheels were a much more stable frame than the tottering “high-wheel,” dramatically reducing the danger and difficulty of cycling. The bicycle’s popularity within the Continent, particularly in ever-fashionable Paris, imbued the product with a measure of prestige and glamour it had never before enjoyed. It became a must-have status symbol. In 1898, one Frances Abbott, quoted in The North American Review, remarked: “I have lived to see the woman who never wished her daughter to have a bicycle ride a wheel herself in company with that daughter; and when I ventured to recall her former opinions she said with unblushing serenity: ‘Oh, well, everybody rides now; the most fashionable people have taken it up; there is really nothing like it,’ and she began to chide me because I did not own a wheel.”

The bicycle craze was more than just a pure product of fashion and modern mass consumption, however, and it wasn’t necessarily an expression of progressiveness. The bicycle was adopted into a middle-class culture (the wheel was far too expensive for most of the working class, at least initially) that remained solidly Victorian in outlook, ridden by people whose perspective was founded upon rigid dichotomies between “right” and “wrong,” “man” and “woman,” “authentic” and “fake,” “respectable” and “not-so-respectable.” The bicycle served to bolster these Gilded Age principles in the hands of its users, functioning as a mobile platform on which its owner’s genteel credentials could be displayed and proven.

One way of doing this was to buy the most expensive, luxurious and tasteful bicycle and accessories possible. From decorated chain-guards to novelty cycling bells to handle-bar revolvers, consumers spent more than $200 million on bicycle sundries in 1896 alone, as opposed to only $300 million on the bicycles themselves that same year. Nowhere did the consumer culture surrounding the bicycle manifest itself more than in the area of attire. By sporting the latest styles, wheelmen and women sought to project a public image of taste and wealth for their peers to appreciate. In 1898, The New York Times wrote that “Sweaters…will probably be seen but little among the better class of riders this year, as the extra comfort gained by their wear is considered more than offset by the impossibility of preserving a spruce appearance when wearing them.” A well-meaning author pressed home the point in The American Cyclist, declaring that “I cannot repeat too often that, in matters cycular (sic), STYLE IS PRACTICALLY EVERYTHING; without it, strength is wasted, appearance sacrificed, and pleasure lost.”

Style was at the center of the cycling promenades and parades that drew thousands of riders and even greater crowds of spectators to the boulevards of the city throughout the mid-to-late 1890s. The most popular setting for these displays was Riverside Drive — the “paradise of bicyclists” in New York, as Harper’s Weekly labeled it in 1894. The New York Times reported that “the Sunday procession of cyclists has got to be one of the sights of the city,” and the great collections of cyclists who gathered every weekend was described by reporters as a kind of formal spectacle — a “procession,” a “pageant,” a “parade.” Such terms were a result of the emphasis on presentation and display that, above all, distinguished middle-class cycling from more utilitarian travel.

But decorum and propriety had to be satiated as well, and too much tactless display simply would not do. The Brooklyn Eagle warned potential parade-goers that “no fancy or fantastic costumes will be allowed in the line. Bicycle riding is a matter of common sense, and it should not be brought into ridicule by the fantastic notions of any few individuals who may have adopted it.” And while much has been made of the liberating effects of cycling on women’s dress — iron corsets and unwieldy skirts were disregarded in favor of more form-fitting, sensible wear while a-wheel —

Along with their appearance, the comport and activities of cyclists were subject to genteel regulation. “Scorching,” or riding extremely fast, was seen as not only dangerous, but a sign of low-class loutishness. The New York Times reported that “with the cheapening in the cost of bicycle riding in the public streets has come the abuse of that privilege by thousands of ignorant and loaferish individuals… irresponsible and reckless young men to whom a stable keeper would not entrust a saddle horse, and who are not fit to ride anything but a rail.” Several dozen cycling schools and innumerable etiquette guides were produced which would help the wheeled bourgeoisie not only learn to ride, but “ride right.”

The bicycle was a private vehicle in public space, and hence a topic of moral and political import. Opponents of the bicycle claimed that the wheel undermined morality (amongst other things, by enabling young women to venture great distances without supervision), caused noise and interfered with traffic. Conversely, bicyclists claimed that “the more ignorant, uncultured, and generally illiterate and ‘countrified’ the man is, the more bitter is his hatred of the bicycle” — and lobbied for bike-friendly legislation, paved roads and additional bicycle lanes. (Sound familiar?) The Brooklyn Eagle declared in 1896 that “thousands of men, women and children who ride on bicycles are aware that they have the same right in the roads and streets and alleys of this country that the walker and horseback rider and wagon and truck driver enjoy.” Through the efforts of the League of American wheelmen and several other clubs, many of New York’s cobblestone streets were made more bike friendly through the mid-1890s by being paved with macadam — single layers of small stones — along with some of the first dedicated bicycle lanes in the country.

Students taking the bicycle to Kingsborough today.

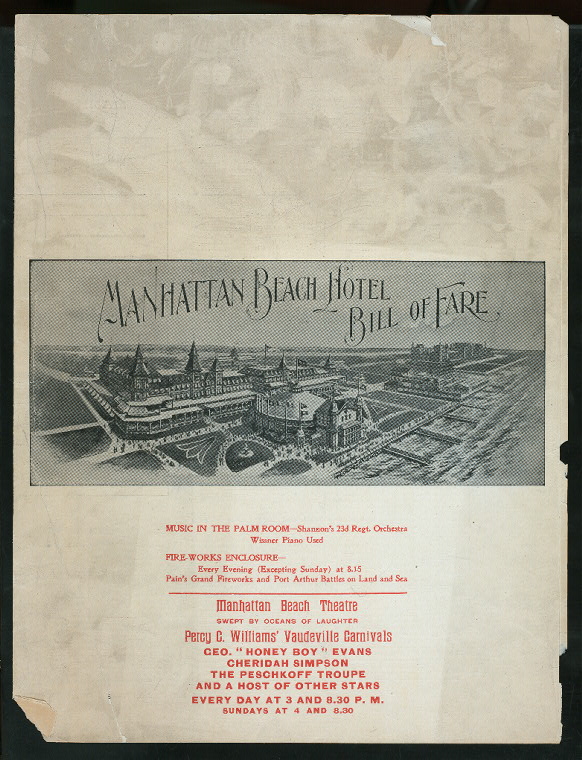

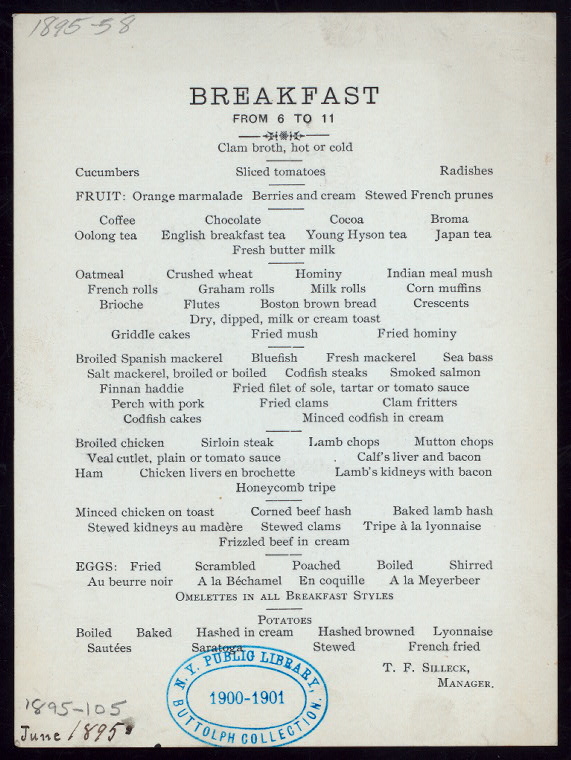

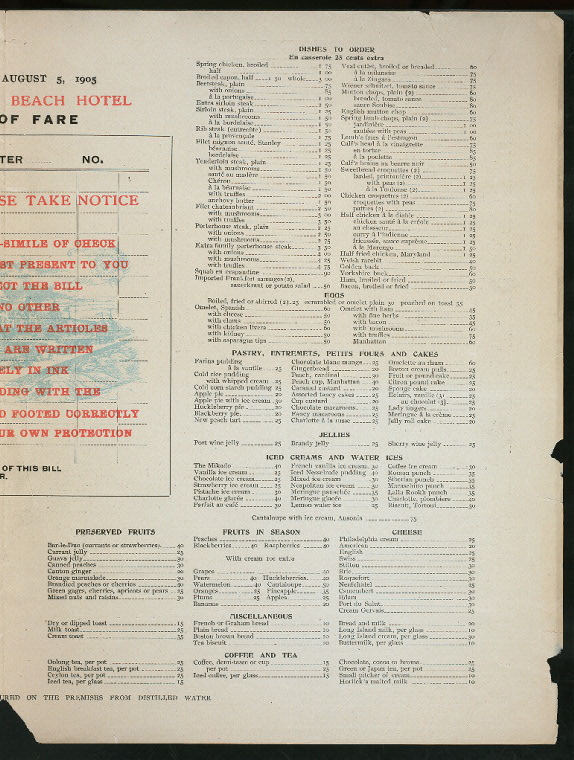

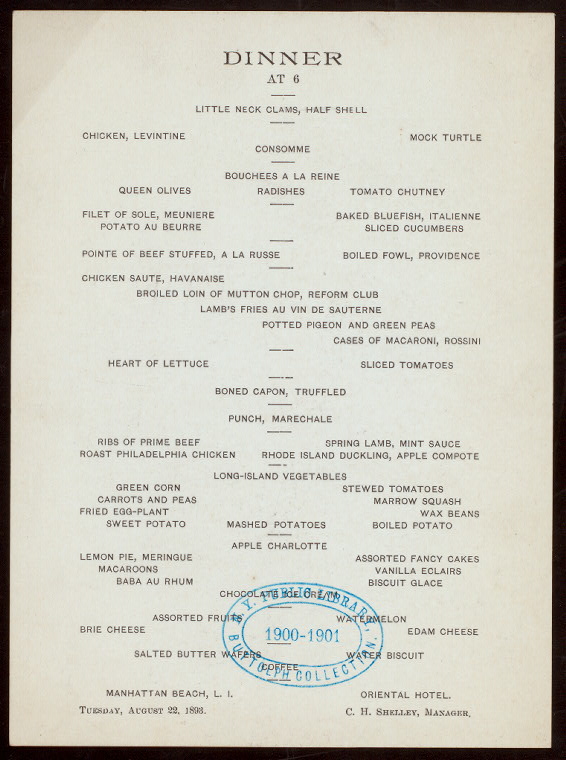

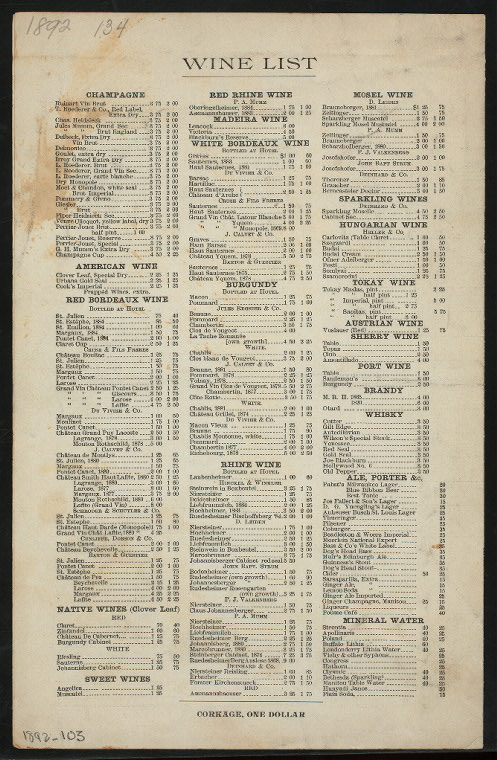

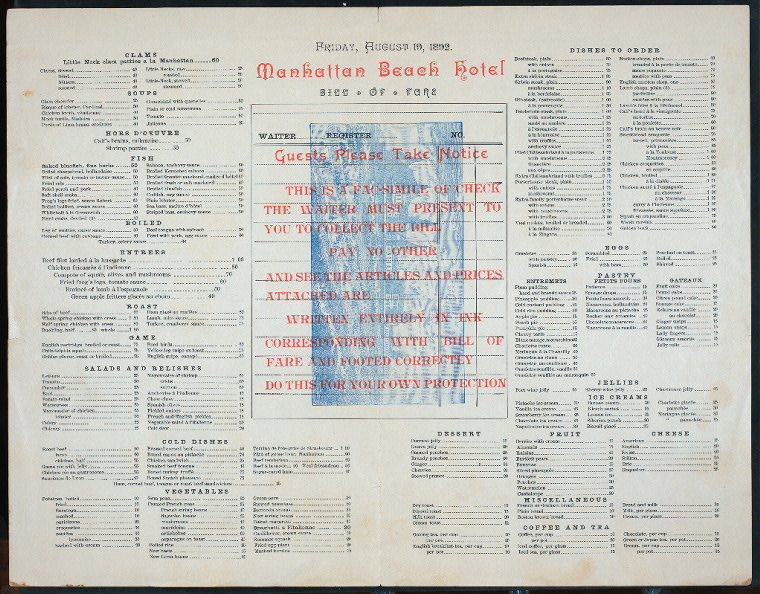

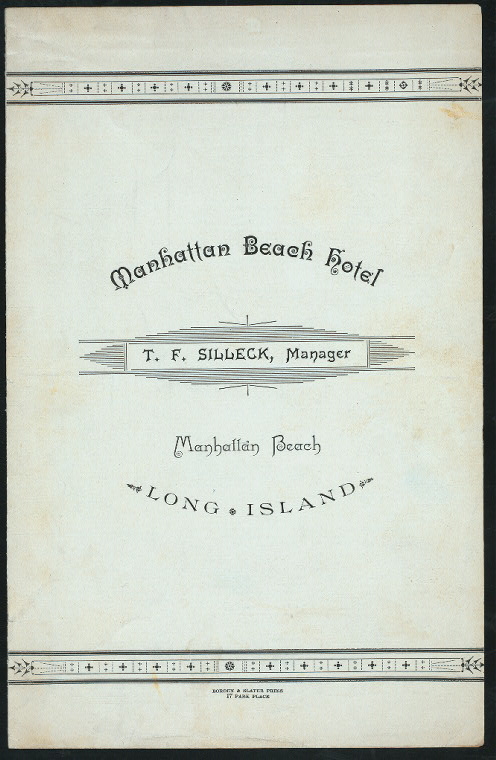

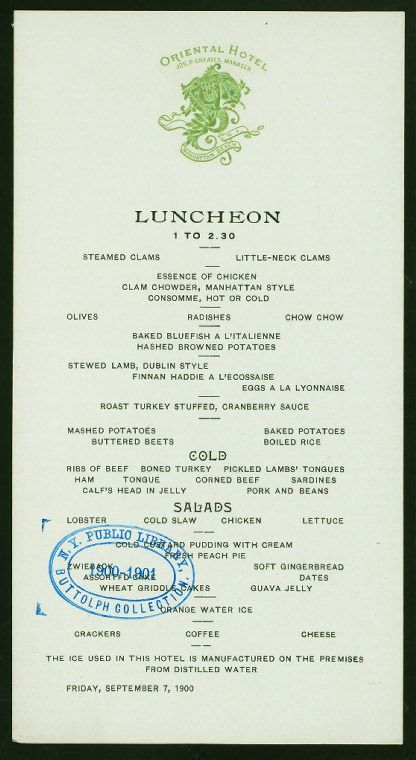

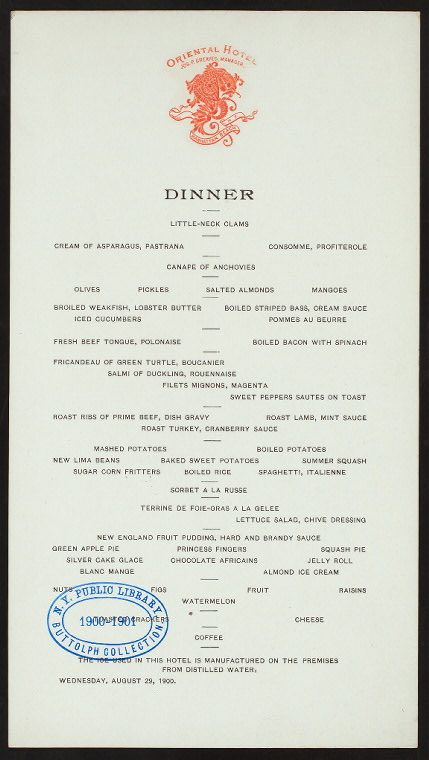

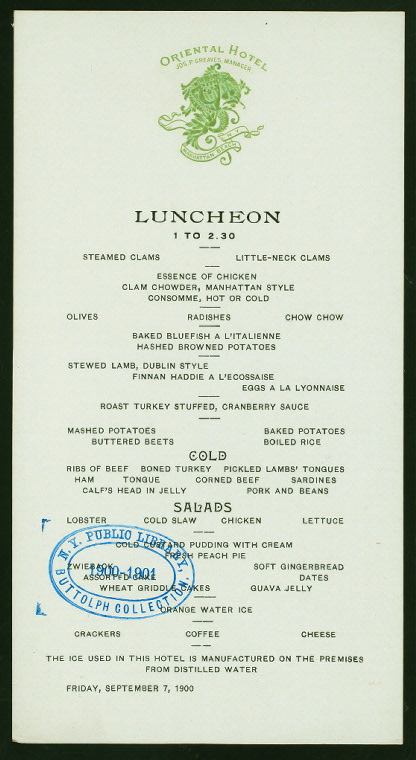

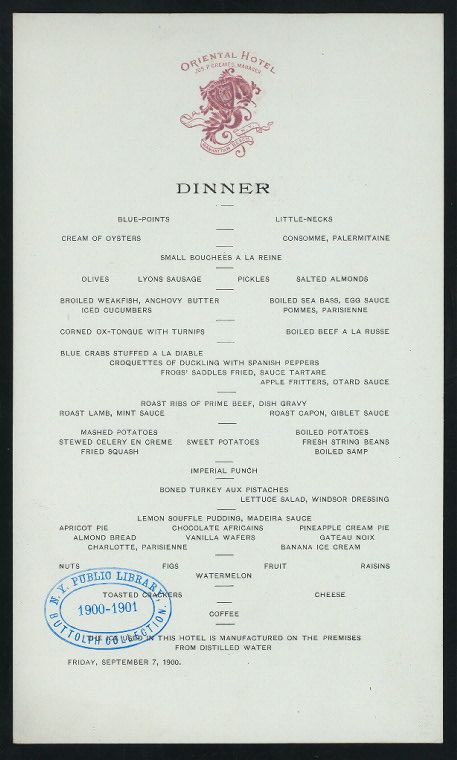

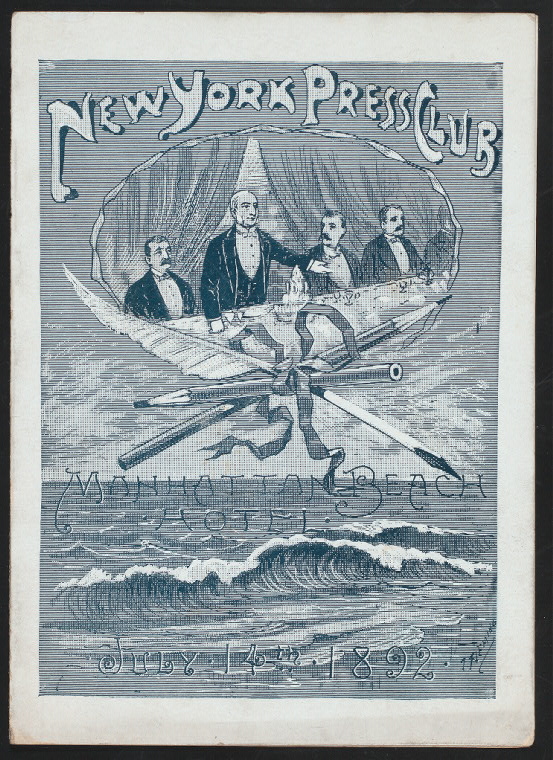

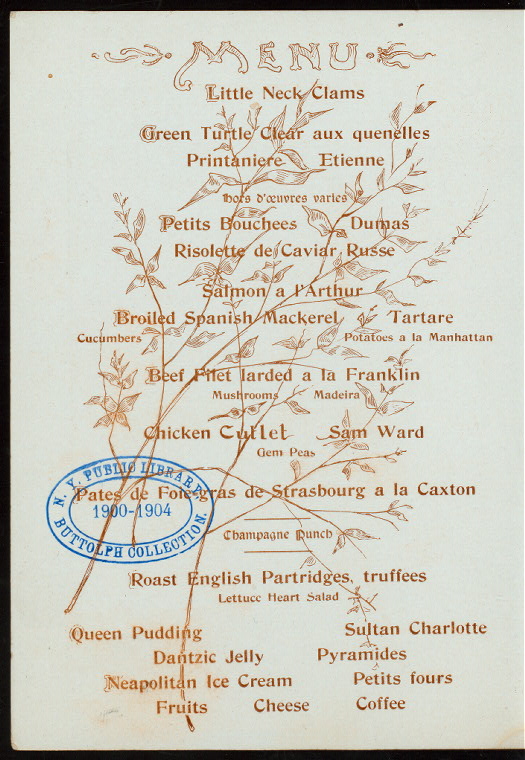

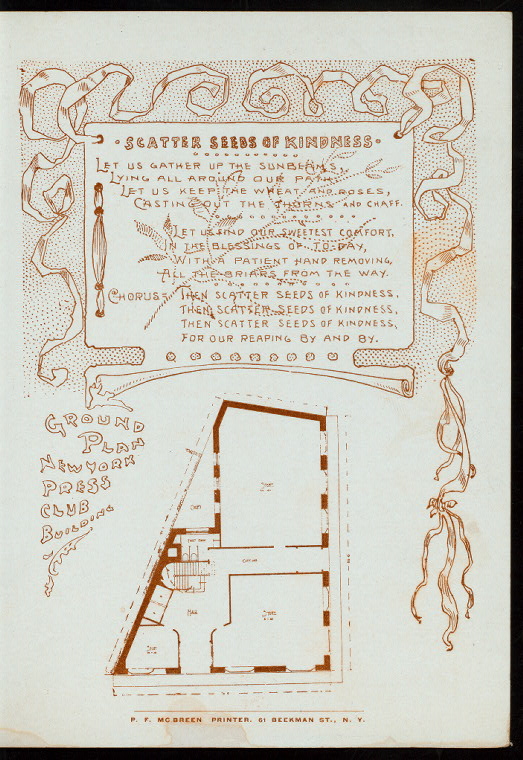

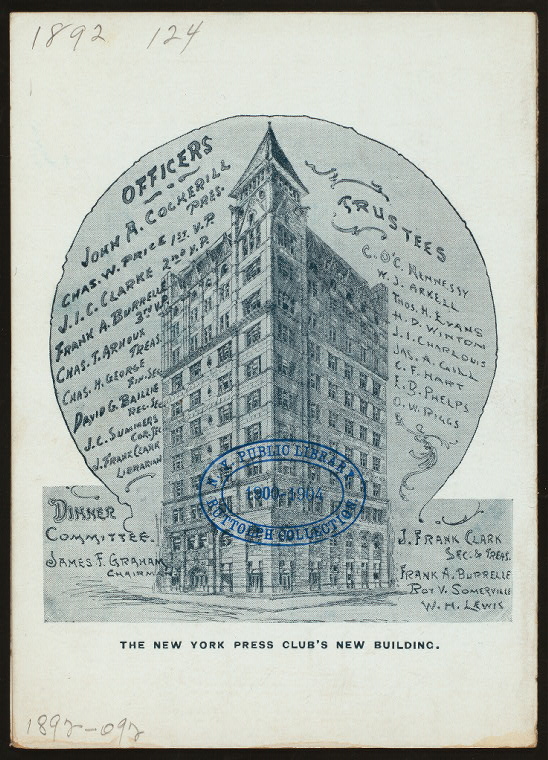

The Gastronomic Guide to 19th Century Brooklyn (Manhattan Beach), now Kingsborough

How the grand seaside resort hotels of the 19th century like the Manhattan Beach Hotel and the Oriental Hotel shaped modern life marked the emergence of a safely curated social sphere, replete with accessible luxuries as temporary cushions against the harshness of modern life. The cultural historian Molly Berger, in her recent book “Hotel Dreams: Technology, Luxury, and Urban Ambition in America, 1829-1929,” suggested that big hotels offered “a city within a city” to their visitors, who paid to live in a dream of perfect surroundings and service for a night, a week, or even a month at a time.

![13239097_10154066405831071_7866758588800282430_n[1]](https://kingsboroughblog.files.wordpress.com/2016/05/13239097_10154066405831071_7866758588800282430_n1.jpg?w=782&h=1043)

Fruit Tart Pie prepared by Kingsborough Community CollegeCulinary students on the same spot where the great Kitchens of the Oriental Hotel and Manhattan Beach Hotel once stood and Manhattan Beach Green Apple Pie was once served in the late 1880’s.

Far from simply offering a convenient place to stay for the night, the Manhattan beach and Oriental hotels conferred social status on their guests, and became centers of social life Socially, they promised something just as modern as their fixtures: the chance at hypermobility. These American grand hotels valued aristocratic clientele, and the glamor that they added to hotels, so much that they sometimes let indigent nobles stay for indefinite periods of time without paying.

![13221070_10154069736471071_4913110454590093461_n[2]](https://kingsboroughblog.files.wordpress.com/2016/05/13221070_10154069736471071_4913110454590093461_n2.jpg?w=924)

Reknowned Chef Emeril Lagasse with todays Kingsborough Culinary Students

The Oriental Hotel located where today’s Kingsborough Culinary Students work in kitchens inside the Marine Academic Center Rotunda.

![KCC_from-the-bay[1]](https://kingsboroughblog.files.wordpress.com/2016/05/kcc_from-the-bay1.jpg?w=718&h=479)

IN 1923 Theodore Dreiser wrote about the Manhattan Beach Hotel of the late 1800’s:

Below are bits of the first two pages of “A Vanished Seaside Resort” (originally published in 1923 in Dreiser’s The Color of a Great City:

At Broadway and Twenty-third Street, where later, on this and some other ground, the once famed Flatiron Building was placed, there stood at one time a smaller building, not more than six stories high, the northward looking blank wall of which was completely covered with a huge electric sign which read:

SWEPT BY OCEAN BREEZES

THE GREAT HOTELS

PAIN’S FIREWORKS

SOUSA’S BAND

SEIDL’S GREAT ORCHESTRA

THE RACES

NOW–MANHATTAN BEACH–NOW

…When Sunday came we made our way, via horse-cars first to the East Thirty-fourth Street ferry and then by ferry and train, eventually reaching the beach by noon.

…Indeed, Thirty-fourth Street near the ferry was packed with people carrying bags and parasols and all but fighting each other to gain access to the dozen or more ticket windows. The boat on which we crossed was packed to suffocation, and all such ferries as led to Manhattan Beach of summer week-ends for years afterward, or until the automobile arrived, were similarly crowded.

…The long, hot, red trains trains leaving Long Island City threaded a devious way past many pretty Long Island villages, until at last, leaving possible home sites behind, the road took to the great meadows on trestles, and transversing miles of bending marsh grass astir with wind, and crossing a half hundred winding and mucky lagoons where lay water as agate in green frames and where were white cranes, their long legs looking like reeds, standing in the water or the grass, and the occasional boat of a fisherman hugging some mucky bank, it arrived finally at the white sands of the sea and this great scene…It was romance, poetry, fairyland.

Kingsboorugh Culinary Program![13237603_10154066653661071_489508790698798572_n[1]](https://kingsboroughblog.files.wordpress.com/2016/05/13237603_10154066653661071_489508790698798572_n1.jpg?w=924)

Kingsborough Culinary Program Students.

Map of Long Island- Kingsborough and Hotels on Western End.

M

![13267720_10154066649261071_2273531009796119043_n[1]](https://kingsboroughblog.files.wordpress.com/2016/05/13267720_10154066649261071_2273531009796119043_n1.jpg?w=924)

The First Trans-Atlantic Cable Began at Kingsborough and Ended in Ireland

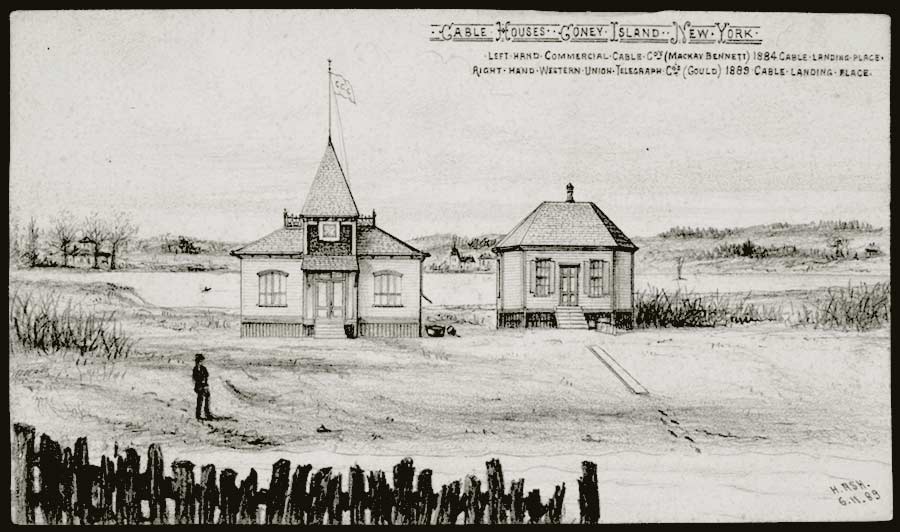

View of the Cable Building utilized by Commercial Cable Company of NYC to Connect with Europe from what is now the point of the Kingsborough Campus occupied by the KCC Arts and Sciences Building- photo from late 1800’s-

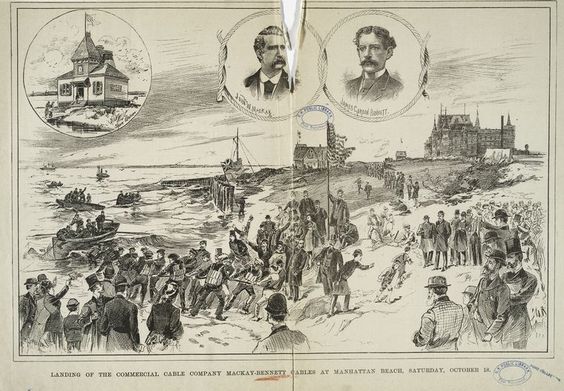

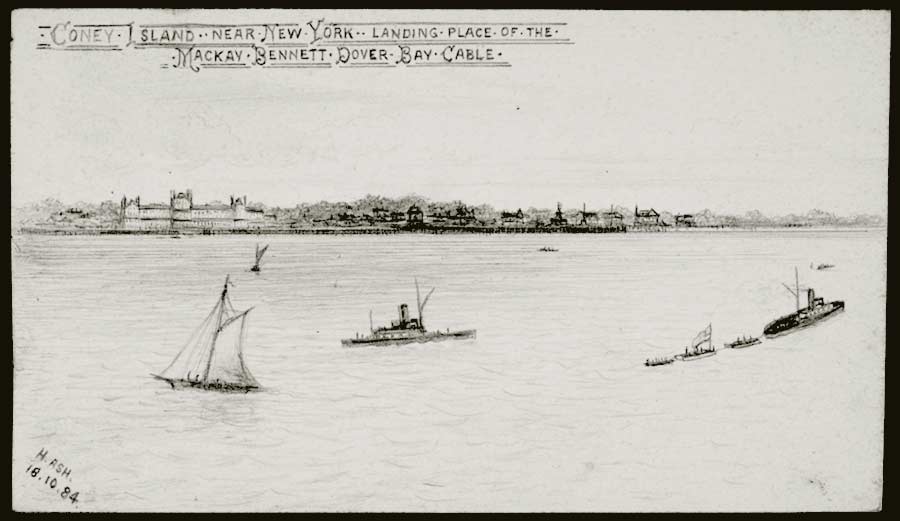

The very first Trans- Atlantic cable line was laid in 1884 from Waterville, Ireland, to Dover Bay, Nova Scotia, and then on to Manhattan Beach, New York (where today Kingsborough Community College now stands). The original landing point was towards the eastern end of Manhattan Beach, the location of today’s Kingsborough Arts and Sciences Building a location also used for subsequent cables operated by the Commercial Cable Company Company of New York.

Drawing of the Original Cables being dragged ashore-in distance Oriental Hotel of Manhattan Beach.

Photo of the Commercial Cable Company building at 20 Broad Street,

New York, next to the New York Stock Exchange were the Original Cable Ended. (The Banker’s Magazine, 1910)

Built 1897, building was demolished in 1954.

According to a report on the Commercial Cable Company published in 1904 by the American Institute of Electrical Engineers the cable houses were situated “one thousand feet east of the Oriental Hotel”, which would place them towards the east end of present-day Kingsborough Arts and Science Building. From there the cables ran under Sheepshead Bay then overland (via the Brooklyn Bridge) to the company’s offices at 20 Broad Street in Manhattan.

The route of the cable across Brooklyn is described in this 1899 article below in theNew York Times. Oddly, an article from 30 August 1894, also in the New York Times, reports that this land route was about to be abandoned by the CCC because of electrical currents from trolley cars interfering with the telegraph signals, to be replaced by an extension of the undersea cable from Coney Island around to New York Bay and up to “Pier A, North River”

Drawing of the Cable Building connecting Europe with America ( Manhattan Beach, Brooklyn)

As bathing in the ocean increased in popularity during the nineteenth century, the east end of the island—farthest from the city and at some distance from the rougher sections to the west that were popular with the urban working classes—quickly became an exclusive retreat, with several lavish hotels lining the mostly privately owned beaches. Establishments such as the luxurious Oriental, for the very rich, and the Brighton Beach Hotel, for the well-to-do Brooklyn middle class, opened in 1876 and 1878, respectively, and provided their own ferry and railroad connections with Brooklyn and New York. Private detectives patrolled the grounds for security. Music and fireworks entertained thousands of guests at night, and the restaurants could accommodate up to twenty thousand diners every day in the summer season. Today this section is known as Brighton Beach and Manhattan Beach, where Kingsborough Community College now stands close to the site of the former Oriental Hotel. The Trans-Atlantic Cable was only a few hundred yards from the Oriental Hotel.

.

.

Oriental Hotel <Manhattan Beach- the Cable Building stood to the left and back in this photo. The Oriental Hotel is approximately where the Marine Academic Center Building now stands.

From the New York Times 1899-

THE END OF AN OCEAN CABLE

“WITH a cigar in his mouth a quiet, keen-eyed, bearded gentleman sits daily, very often at night and on Sundays, at a roll-topped desk high up in one of the tallest of New York’s office buildings. Hundreds of other men of far down town sit at similar desks, alike meditative and at the proper moment alert. But the task of this one man is far different from those of the hundreds. A few steps away from his seat stands a table covered with many delicate registering instruments, the precise uses of which a layman can only conjecture. A cloth is swung on wires overhead, to be let down when no one is at the table. Turn in the other direction from the desk, and through a door is to be seen a miniature electric workshop.

There is nothing imposing in this corner far aloft, away from the madding crowd of curbstone brokers, of industry and science, but a peculiar interest attaches to it nevertheless. For at the table of many instruments several of the great Atlantic cables have their American ends. The self-contained man mentioned can sit here and test any one and all of half a dozen ocean telegraph lines. What is more, he can tell, if not to an inch, at least within a few miles, in a length of many hundred just where any cable is broken or injured. It happened a few months ago that there was a break on one of the West Indian cables. After testing this the Superintendent marked out on the chart about where he thought the break was. The repair ship that went out found it was actually within a mile or so of the point indicated.

Precisely where the cable does land in New York is a question that is only to be answered in half a dozen different ways. What is practically its real termination Is not at all imposing. In one of the two great cable companies’ buildings there is a closet, or shallow room, on the ground floor, hidden away behind the great switchboard. Here, in one sense, this company’s Atlantic cables terminate. But quite as much do they end, unostentatiously, on a table in the big general operating room a few feet away, looking like any ordinary telegraphic instruments. Again they end, in a fashion, in the Superintendent’s office, as described above, that official, as it were, being able to pick up any cable in an instant. And, moreover, from yet another point of view, these ocean cables really end or land on the far northeastern coast up by Newfoundland, the cables that run into New York being, with the exception of the West Indian, purely subsidiary or secondary cables, coming round from the region of the “Banks” by skirting the coast. Deep sea cables they are most certainly, but not the veritable cables that stretch under midatlantic waters.

A cable directly into New York is in reality quite a new thing. Scores, hundreds, thousands of cable messages come even now part of the way by land, being sent on from a point near Halifax. There was a time when all cable messages traveled that way, and were subject to delays along overhead wires affected by weather. The outermost Eastern provinces of British North America are a very far cry from the United States’ commercial centres. It was a stroke of business genius that first put the theory of a cable “all water route” in the mind of a man. Now there is more than one of them, and even a cable that takes the “all water route” so literally that it comes up New York Bay, striking land among the wooden beams under Pier A, North River.

Far Manhattan Beach—that is, the remotest eastern point of it, out in the midst of the sand that even the most venturesome frequenters of the great hotels seldom venture upon—is the first bit of American (not British-American) soil the cables to New York touch. (To be strictly accurate. an exception must be noted here, one of the cable lines having its American terminal at Cape Cod.) Along this strip of beach there are two little houses, one a hut, the other hardly more than a hut. It is within these that the cables of the two chief companies come up from the sea. Thence in trenches they run underneath Brooklyn and across the bridge, with the exception of one—already mentioned In the paragraph above—which, having come to land, leaves Coney Island directly, plunges again into the sea, and finds its way up to New York’s Battery along the bottom of both the Upper and the Lower Bay.

It is more than worth the while to follow foot by foot one of these bunches of wires that have such mysterious powers, to track it from the clicking instruments that lie on a table in the great message-receiving office to the little house at Manhattan Beach, where, finally disappearing beneath the floor, it makes its way below the waves to the ocean’s bottom.

All the more worth the while is it, indeed, for the reason that we soon may hear that cable laying was a useless affair after all: that no electric message of the future will need a metal carrier, but can breast the waves or the air alone, quite accurately, quite in safety.

A technical explanation of the marvelous group of instruments that in this office of the Superintendent, once a week at all events, read the health of each cable is, it must be admitted, beyond the capabilities of the writer. And were such an explanation given It would be beyond the understanding of the average reader. Only a skilled telegrapher could appreciate the exact significance of all that is done at these tests. In brief, it is simply this: A wavering needle incased in glass registers as the cable, at rest for the moment, shut off from the service, has certain electric currents passed through it. The needle is the pulse of this long cord of wire. With never-failing accuracy it makes answer, telling not only how the cable is, but where the seat of possible trouble may be. The cable doctor does not wait until something goes wrong; he keeps his miles of submarine wire under observation and notes every symptom.

There lay a marvel of modern machinery for the onlooker. Hundreds of miles away the sender had “put” these messages “on the wire.” No human hand had had anything to do with them since. Of themselves they now lay printed on the long tape in New York. And in succession came others, perfect records that went to show the absolute obedience of the genii of electricity once subjugated.This one cable that writer and photographer followed from its very end to the last glimpse of it on land terminated in a great Broad Street office building. To speak with something resembling technical accuracy, it was not the cable itself that the Superintendent and his assistant were engaged in testing far up stairs, but a wire connecting with the cable. That stood for precisely the same thing. The real end of the cable, according to the way the operator looked at it, was on a certain receiving and transmitting table in the general office. At one side of this a man sat sending, at the other a man receiving, messages. Both tasks seemed extremely simple. The messages came not with the tick and the click commonly associated with everything telegraphic, but silently, automatically, on a thin strip of white paper, (ticker paper,) that, shut up in a curious glass-covered machine, narrow, long, a mass of wheels and of cogs, gradually unwound itself and appeared printed, in telegraphic characters before the operator’s eyes.

Close to the man who was “receiving,” and close to this glass-covered case whence the tape came, the “recorder,” was a telegraphic instrument of the ordinary variety. As quickly as this man could read the printed tape he telegraphed the message along. To where? To a chair not three feet away on which sat a second man before a typewriter. The other end of this shortest telegraph line in the world ended in a box close to the second man’s ear. The clicks thus came to him distinctly, and as the message sounded the words were promptly set down on his typewriting machine, ready In an instant to send out by a boy.

The sending of cablegrams was no less simple. Here, again, a tape played a part. As each message to be transmitted came in a boy took it, and by a punching machine set it down on a length of tape along with others in the Continental Code. Translated now telegraphically into a series of holes punched into the tape, showing by their arrangement the dots and dashes of the cable, the message was now ready for transmission.

Behind the switchboard spoken of the cables, important commercially and telegraphically as they were, took up little space. They came to sight in a little box on the wall, a box with two glass doors. Behind the switchboard there was many a bristling wire, many a key and bit of metal. But the cable box showed almost nothing, save a few bits of covered wire. Particularly interesting were the printed notices on the little doors. One of these read, “Coney Island; do not open for Hayti,” the other, “Hayti; do not open for Coney Island.” Strange as it seemed, the mere opening of one of these little glass doors “cut out,” that is “broke,” a cable for the time being, the keeping of the door closed “cut in,” or made the connection.

The onlooker had, in fact, to take it on faith that here was a terminal of some of the mightiest of ocean cables. He felt more as if he were genuinely in the land of electrical and telegraphic mystery when he was ushered into a room in the far distant basement in which staffs of twisted wires, heavily coated, arose out of the floor. But even here the great cables made but a poor showing. Out of scores of these staffs of thick wire that, planted closely together, a forest in a room, shot from floor to ceiling, only two, and these seemingly the least significant, were the cables. Indeed, a proper sight of these ropes below the ocean must be sought elsewhere.

“Here’s where they go underground, Sir,” the workman was saying as he wiped his moist face with the most available rag, adding new streaks to the old. “They come out right under Broad Street. Unless the street is torn up somewhere you won’t see ’em again until you get to the Bridge.”

Then began a long and interesting journey of following the cable in its land course down to the little house on Coney Island’s sands. Once it is buried beneath the waves, a cable needs no guard, but on land it is a very different matter. In a trench a foot or so beneath the surface of the ground it is at the mercy of many an accident of city life. A chance blow from an ignorant Italian’s pick in street tearing up may half sever the pulsating stretch of metallic ribbon. Few people, even the foremen of street repairing gangs, seem to realize the presence of the cable in New York and Brooklyn, few think of its whereabouts, if indeed they know about it, few give it any heed.

A constant patrol is necessary. This company has a man who gives two-thirds of his time to tramping over the “line.” He starts out from Broad Street at noon, and follows the cable’s course, keeping an eye on all street work, warning foremen and workmen whenever it may be necessary, Sturdily and faithfully, day by day, does he go over the ground. It is seldom that he finds any danger menacing this land line, seldom that be has to send word to the office of any actual trouble, only two or three times a year that he needs to call for a gang of men to make repairs. The ounce of prevention here is worth many pounds of cure.

It was with this man, who thought nothing of a dozen miles of patrol a day, and to whom this cable was as a favorite child, that the writer and photographer journeyed one hot Summer afternoon. The route lay from the Broad Street building, under Broad Street to Water, under Water Street to under the shadow of the New York anchorage of the bridge. All this while the cable was beneath the travelers’ feet, but invisible. It seemed that, considering its delicacy, its importance, it was very slightly protected. One would imagine a casing of stone and cement for an implement of this sort that a thoughtless blow might injure, but on the contrary it was resting a few inches below the ground, in an ordinary six-inch pipe.

Experience bas gone to prove, however, that this all that is necessary. This particular cable has been down for fifteen years, and during all this time it has sustained practically no injury. The inspection day by day guards against this.

A mass of creels of telephone wire—a telephone company storing here—of dirt, and confusion is the New York anchorage yard of the Bridge. From here the massive construction of that great structure can best be appreciated. Up the great blocks of stone that towered overhead, growing unostentatiously out of the ground, two threads dingy in color could be seen climbing. side by side. These were the two great rival cables, burled under streets for a mile and more, now to cross the East River on their way to Coney Island. Out of their piping now, wrappings and all, they were but some three inches in diameter each. By the time they reached the under side of the promenade, to journey from shore to shore, they were but one and an eighth inches in diameter, slender ropes that gave no hint of their weighty duties.

The average man, the average woman, probably has not, probably would not notice these cables as they cross Brooklyn’s bridge, yet they swing in plain sight, two discolored ropes under the promenade, easily to be seen from the platform of either bridge or cable car. Down the stone of the Brooklyn side anchorage these cables drop in precisely the same fashion. Both again disappear underground. The cable the writer and photographer are following takes a devious course in its ten-odd miles through Brooklyn and Brooklyn’s suburbs. For some blocks, always only a few inches below the street, generally lying close to the curb, it rests in a two-and-a-half-inch iron pipe. Then it runs in a five-inch pine box, the boards being two and a half inches thick.

Beyond here along Vanderbilt Avenue to Prospect Park Plaza the construction changes again. The cable is now in a trench, covered over with a creosoted pine plank, ten inches wide and two and a half inches thick, with side pieces of board of the same thickness. From Prospect Park on the cable has no protection at all. It is simply laid in earth, and proceeds down Flatbush Avenue to Ocean Avenue, then under here in a straight line to Sheepshead Bay, where for a few feet it takes the water, coming out on the Coney Island sands under the cable hut.

If all is well with the cable, there is nothing to be seen in this ten-mile journeying. Accident is the only thing that exposes it to view, and months go by without more of it being visible than a bit of the box here, an end of board there, a stretch of piping elsewhere, during some street repairs or some high revel of workmen with gas and water pipes. The testing apparatus in the room described above can tell whether all is well along its entire length.

A workroom on one side, a storeroom on the other, with cots and blankets, for sometimes it is necessary for men to stay down here days at a stretch, comprise the entire outfit of the cable house on the beach. In this workroom it is that the cables appear to their best advantage. Black and bristling at their points or connection with many wires, they show against one of the walls of the room, half a dozen and more in all, some up from the ocean, having passed through the sand and under the house up through the floor, others on their way to New York, via land, or, as in the case of one, by direction of sea.

These are, after all, the genuine cables, the cables caught wild in their lair, for in this room they are seen wrapped in their ocean sheathing. Here it is that the cable gives evidence of its power, shows its strength and its trustworthiness to bind together two continents. And, as the expert electricians on duty, garbed in workingmen’s clothes, with many a dexterous twist and turn, harness one cable here to this land line, attach another, cut off yet another, splice and bind, recoat and make their joinings, all in obedience to the clicking of the messages that come to them from the Superintendent in Broad Street, who holds all of these wires literally in the hollow of his hand, one can only feel that a great magic lies in it all—the magic of the science that is of to-day.

These cables’ sheathings are wonderfully Interesting. First, there is stranded copper coil in a cable, insulated with pure gutta-percha. Over this is stretched a cushion of Russian hemp, and outside still, for protection against the elements of the deep, there is steel wire. Near shore—that is, five or ten miles out—a cable has a double coating of “armor” for better guarding against the waves. Two to two and a half inches in diameter are the dimensions of a cable near shore, one inch that of a deep-sea cable. At Canso the cables have ferrules, or rings of steel, to protect them against ice.

It is only when the cables that come from the sea need changes in connection with the “land lines” that men come to this cable house. At times the little building may he deserted for a week: again, it may be visited every day. When the cables keep in proper trim there is little to be done at Coney Island. Yet, on the other hand. these men have known a week of hard and constant work in the Winter here, on guard day and night, when storms were blowing fiercely and all else of Coney Island was deserted, the workers’ food on these occasions being mainly “canned goods.”

“Put the main cable on No. 3 underground.” This message comes in clicks from the Superintendent in New York, and the men are alert. There is a connection to be cut apart, the “land line” and a sea cable to be severed, a sharp jab with swift cutting of knives and untwisting of wires. Even more knack is required in the joining. Two lengths are dangling, to be welded into one strong rope. The solder is softened with a lamp, and dexterously the “joint” is made. There must be neat and close fitting to prevent high resistance in the circuit. Wood alcohol is poured over to remove the acid used in this soldering.

The “joint” is, so to speak, made; the cables have become one. Yet there is still much to be done. Harrington, the workman, smears on “Chatterton’s compound” (Stockholm tar, gutta perches, and resin.) to make the gutta percha adhere to the wire. Heated glue is as nothing to this combination. Harrington has to moisten his fingers constantly to prevent the gutta percha from sticking to them. With tool after tool, with turn and twist, the joining is welded into a single mass. One would never know that this rope was a few moments before two distinct cables.

Finally he drops the now completed rope and nods his head. The man who has been helping has his finger on a telegraphic instrument. “Tell him Coney Island’s O.K.” says Harrington.”

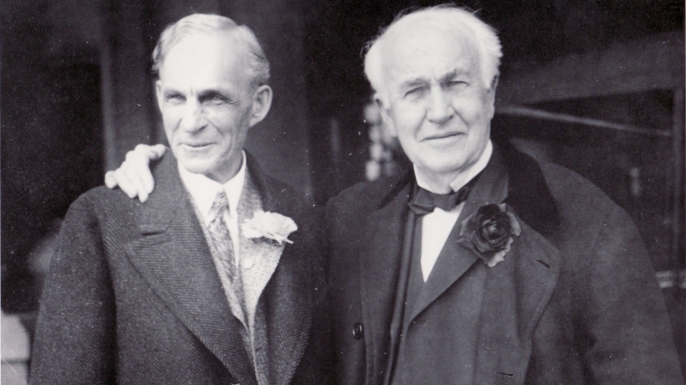

When Thomas Alva Edison first met Henry Ford -the Friendship that Changed History -at Kingsborough Community College , Brooklyn

It came at the end of the main banquet at the 1896 annual meeting of the Association of Edison Illuminating Companies, AEIC. The setting was the stately Oriental Hotel in Manhattan Beach, in Brooklyn, New York now the location of the Kingsborough Community College’s Marine and Academic Center Building ( and Coast Guard certified lighthouse). A group of the nation’s top technical and business leaders remained at their table to smoke cigars and talk of the events of the day.

AEIC was founded in 1885 at the dawn of the Age of Electricity. At the 1896 meeting, forty-four powerful men from eighteen illuminating companies were in attendance.

Thomas Alva Edison sat at the head of the table. He was flanked by officers of the nation’s largest power companies.

There was Samuel Insull, from Chicago’s Commonwealth Edison. Insull would become the father of utility regulation.

There was John Lieb, from New York Edison. Lieb had been the first manager of Pearl Street, the world’s first central generation station. And he was then instrumental in the development of the electricity industry in Italy.

There was John Beggs and Alex Dow, from Detroit Edison. Beggs, an accountant and director of numerous companies, developed many of our methods in depreciation accounting.

Years earlier, Beggs had wanted to electrify his church to save the costs of candles and cleaning them. He was head of the church’s building committee. It became the first worldwide to be wired and electrically-lighted.

The titans of the new electrical industry talked of developing electric vehicles. It had been the topic of the afternoon session of papers presented that afternoon.

At one point, Dow pointed to his chief engineer, Henry Ford. Ford was just thirty-three at the time.

Dow announced, in Edison’s direction, “There’s a young fellow who has made a gas car.” Everyone wanted to hear more. Ford had just completed his Quadricycle.

Taking the chair next to the nearly deaf Edison, Ford described his prototype gasoline-powered carriage and showed him his plans. This was the first time the two had ever met. When he finished, Edison “brought his fist down on the table with a bang and said, ‘Young man, that’s the thing; you have it. Keep at it.’

Photo of the Oriental Hotel ( above) located in Manhattan Beach, Brooklyn ( now the site of Kingsborough Community College ) this is where Thomas Edison first met Henry Ford.

Edison held his annual summer conference for the Engineers in his Electric company right here in Bklyn, ever year by the shore- knowing this -a young Henry Ford who was facing bankruptcy with his fledgling automobile company attended for a chance to speak with the great man -Edison.

In 1891, Henry Ford left his small lumber business to work for the Edison Illuminating Company in Detroit.

Ford recalled later that Edison’s “bang on the table was worth worlds to me. No man up to then had given me any encouragement.”

The Oriental Hotel, Manhattan Beach, Brooklyn- where Ford first met Edison.

Henry Ford attended the 1896 meeting of the Association of Edison Illuminating Companies in Brooklyn, New York with camera in tow. During the convention, Ford captured several candid shots of his boyhood hero, Thomas Edison.

He also had a personal encounter with Edison at a banquet — a brief but encouraging landmark in the ambitious engineer’s climb- he left the electricity industry three years later, devoting all his efforts to developing automobiles. His Model T debuted in 1908, and sales were booming by 1914. He always credited that meeting with Edison in Brooklyn as the encouragement he needed to continue on his path in the automobile industry.

At that momentous meeting in 1896, Edison was forty-nine, sixteen years older than Ford. Yet the two great inventors forged a lasting friendship of thirty-five years, lasting until the Wizard of Menlo Park died in 1931.

On August 15 , 1899, in Detroit, Michigan, Henry Ford resigned his position as chief engineer at the Edison Illuminating Company’s main plant in order to concentrate on automobile production.

Henry Ford left his family’s farm in Dearborn, Michigan, at age 16 to work in the machine shops of Detroit. In 1888, he married Clara Bryant, and they had a son, Edsel, in 1893. That same year, Ford was made chief engineer at Edison. Charged with keeping the city’s electricity flowing, Ford was on call 24 hours a day, with no regular working hours, and when not working could tinker away at his real goal of building a gasoline-powered vehicle. He completed his first functioning gasoline engine at the end of 1893, his first horseless carriage, called the Quadricycle, by 1896.

Henry Ford working at the Edison Illuminating Company in Detroit above:

In the summer of 1898, Ford was awarded his first patent, in the name of his investor and Detroit’s mayor, William C. Maybury, for a carburetor he built the previous year. By the middle of the following summer Ford had produced his third car. A much more advanced model than his two previous efforts, it had a water tank and brakes, among other new features. Maybury’s support, combined with Ford’s bold ideas and charisma, helped assemble a group of investors who contributed some $150,000 to establish the Detroit Automobile Company in early August 1899.

Ten days later, Ford left Edison, where he had worked for the previous eight years. He turned down a considerable salary offer of $1,900 per year and the title of general superintendent to become mechanical superintendent of the new auto company, with a salary of $150 per month.

But that first meeting was just the beginning of a life long friendship and mutual admiration society between Ford and Edison. Ford for years afterwards would call Edison ” the greatest man he had ever met”.

Henry Ford and Thomas Edison became good friends later on in their lives and were in daily communication throughout the decades . They often camped together, they presented each other with lavish gifts, they owned houses immediately adjacent to each other- they became like father and son.

Edison and Ford famously went on annual camping trips from 1916 through 1924, along with Harvey Firestone, who largely founded the tire industry, and John Burroughs, the great naturalist. During part of the 1921 trip, the men were joined by the President of the United States, Warren Harding.

(Snapshot by Henry Ford of Thomas Edison Asleep at the Oriental Hotel, Manhattan Beach, Brooklyn, New York, 1896)

The photo a top is from the Henry Ford collection- Ford snapped it of Edison asleep on the porch of the hotel overlooking the Atlantic .

Henry Ford had attended the 1896 meeting of the Association of Edison Illuminating Companies in Brooklyn, New York with camera in tow. During the convention, Ford captured several candid shots of his boyhood hero, Thomas Edison. He also had a personal encounter with Edison at a banquet — a brief but encouraging landmark in the ambitious engineer’s life that led to decades of encouragement and friendship.

The number one inventor/industrialist of the 19th Century Thomas Alva Edison met the number one industrialist of the 20th Century, Henry Ford, right here in Southern Brooklyn in 1896 at the Oriental Hotel (where Kingsborough now stands) and it changed the history of the world.

1878 – O.J. Gude started O.J. Gude Company with $100 in capital in Brooklyn, NY as outdoor advertising company; May 1892 – pioneered outdoor electric advertising, first use of electric bulbs in billboard sign (13 years after Thomas Edison invented first light bulb); hanged 50 by 80 feet sign on side of Cumberland Hotel above (intersection of 23rd St., Broadway, 5th Avenues), 1,457 lights that flashed: MANHATTAN BEACH – SWEPT BY OCEAN BREEZES; 1919 – Gude’s name on more than 10,000 billboards across U.S.

Edison was very impressed by the young Ford, offered him advice and assistance with his automobile company. Ford often credited Edison with being the spark that kept him going after so many repeated failures.So also began a life-long friendship for the two innovators that lasted until Edison passed away.

Remember also that the Oriental was a restricted Hotel owned by Austin Corbin and Ford was later also know for his virulent anti-semitism which he denied later in life blaming it on a publicity man he hired.

This is the site of their first meeting today -where Ford first met Edison. Now Kingsborough Community College . Notice the Lighthouse at the top of the Marine Academic Center- pretty sure Mr. Edison would approve.

This is just a little bit of Brooklyn/Kingsborough History- that most people don’t even know about. (there is not even a plaque to mark the place where these two giants of industry and innovation 1st met in Brooklyn).

Perhaps one day there will be.

Students attending Kingsborough in 1887?

These aren’t really Kingsborough students, but they are walking where present day KCC students actually walk to classes everyday. This photo is from approximately 130 years ago and is of the Oriental and Manhattan Beach Hotels. To the right is the Bathing Pavillion for the Oriental Hotel and the sign announces the evenings entertainment of Fireworks and Live Music.

Photo is from the Kingsborough Historical Society founded by Professor Emeritus, and KCC Foundation Inc. Board Member, as well as former Brooklyn Borough Historian and noted author, John Manbeck.

Photo is from the Kingsborough Historical Society founded by Professor Emeritus, and KCC Foundation Inc. Board Member, as well as former Brooklyn Borough Historian and noted author, John Manbeck.